Oh goody! A thread on the Big 5 model. This is my jam

. Maybe I can help answer some of these questions

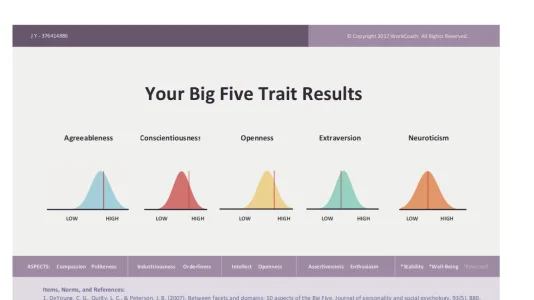

Generally speaking, I am not a fan of the Big 5. I find it overly simplistic and presumptive. My view is that each of the five aspects (tendencies) outlined in the model are too complicated to simply be placed on a sliding scale. For example, if someone scores 67% on "Conscientiousness" or 35% on "Extraversion," those data points alone don't tell me much of anything about their personality. Big 5 would tell you that someone who scores high in Conscientiousness probably performs very exacting work and keeps a neat and orderly workspace, when in fact one isn't necessarily an indicator of the other.

Even the questions presume a great deal; many of them seem vague at least to some degree. I realize that this is probably by design (i.e. how you answer the questions in concert is what's important) but it still seems disingenuous and simplistic to me.

I've yet to study the aspect scales, but they at least seem to add some much needed depth to the model.

I can't access that free test thru work but I'll try to find an alternate and report back.

You are correct that some questions are vague by design. There's a disagreement in the field about the relationship between behavior and thought when measuring personality. I'm in the thought camp, but I recognize that behavior centered questions help with measurement error better than vague questions (aka I'm sympathetic).

I can also understand why you think that it is a simplistic model. However, it was designed using an approach called factor analysis. What this does is take a LOT of different questions, and determines what questions are answered in the same way. For example, "I like to travel the world" and "I like to see new places" would be answered the same way almost all the time. So, we don't need both of these questions to measure the same construct (openness). Further, each of the big five traits are further broken down into facets. For example, agreeableness is sometimes defined by the following facet structure: trust, morality, altruism, cooperation, modesty, sympathy. This means that people answer questions like "I find it easy to trust others" and "I enjoy helping others" are answered the same way most of the time (both are part of agreeableness), but they are understood in different ways. Fancy statistics let us detect these differences.

In those terms, I've heard of the HEXACO test, which is much more extrensive, but it measures each trait on a scale in relation to other's who have taken the test, and not as a thing in itself.

I'm glad you brought this up, because it transitions perfectly from what I said to the previous quote. The HEXACO model was defined in the same way as the Big five was, except for one difference. Above I mentioned how we use statistical metrics to determine how well a model explains the data. One way we do this is by using what's called an eigenvalue to determine a cut-off point for the number of factors present in the data. There are many complicated statistical approaches to finding this cut off, but an old simple way, called the Kaiser criterion, says that if a model, say an 8 factor model, returns an eigenvalue less than 1, then you are forcing to many factors. Next you try a 7 factor model, then a 6, etc., until you are greater than one. The HEXACO model is debated because this 6 factor model of the same data has an eigenvalue very close to (but less than) one, and other new methods of determining the cutoff of an eigenvalue have suggested it is sufficient (other new methods suggest it isn't). It's on the line, though most researchers believe it isn't sufficient. It also generates a wierd pattern where the sixth factor is nothing more than honesty and humility questions (parts of the agreeableness facet in the big five) while all other factors have many more sub-facets. It may seem more explanatory, but it actually considered to be unnecessary according to the data.

Exactly. Got to love the presumption that if one doesn't enjoy certain kinds of art, they aren't as open to new experiences (or vice versa).

Use of the word "art" is even misleading and based on false pretense. When I read the word "art" the first thing I think of is painting and sculpture, which aren't modes of art I'm especially interested in. But that leaves out music, photography, graphic design and other forms of art that I'm in fact very interested in and love to explore in great depth. There are other vague/misleading questions in this same vein.

I think this points to one of the major failings of Big Five - it's foundation is based in

lexical hypothesis, which largely depends on the brain's interpretation of certain words. Since different words quite often mean different things to different people, I don't see how such a test can produce consistently valid results.

And that's not even getting into how different words can mean different things to different people

at different times. Hell, different times of day! This model would seem to be especially susceptible to biases related to mood or circumstance. Think about how much higher someone would score on "Neuroticism" if they're having a really bad day (an experience shared by literally 100% of the human population).

You make an important observation and I have two comments. First, about the art question, this is because, by the method to determine the factors I describe above, we also get a massive list of questions that most successfully identify each factor (high correlations). It just so happens that enjoying art is very highly correlated with openness.

While the question itself isn't a measure of personality, it is a major indicator of a particular personality trait. Another example of this is that political orientation is highly correlated with greater openness, but many do not use this question as an indicator for a number of other complicated reasons.

For me when I look at those categories I'm struck by the extent to which they seem based on values judgments. On forum we have sometimes discussed the idea that N types are supposedly somehow superior to S types in the MBTI. Comparing these categories to that, it seems a lot more clear that there's maybe some sort of bias involved, it seems more desirable to land on some particular side of the mean. Like obviously, who wants to be called neurotic? Well maybe some people would want that for some reason, but how is it really supposed to help you? Like "OK, I'm neurotic. Now what?" It reminds me a lot of the idea of hysteria. The way that the concept of hysteria was used historically not always to help but also to dismiss or control. "She's hysterical."

I can see why you reached this conclusion, and it is a common misconception. First of all, neuroticism does NOT represent a neurotic personality. In fact, many researchers now refer to the trait as emotional stability because of this very missunderstanding. It is important to remember that these trait labels do not fully capture the underlying facet structure of each trait. There is a LOT more to the neuroticism trait than being hysterical. However, you are also correct that neuroticism is not associated with really any positive outcomes. i think some people have found a very weak association between higher neuroticism and corporate success, but I can't remember for sure. Each other trait has clearer benefits to high and low levels.

There also seems to me to be a bit of an aspect of measuring or describing the personality in ways that are not really intrinsic to the personality itself but of the personality expressed in a social context. The way self behaves or is played out within or according to social expectations in context... Is a personality taken alone really conscientious or not? - I think not, I think that in itself the personality is just "doing its own thing", it's only in the context of a social setting and the expectations of that setting that we can decide whether it is hard working or not. "He's lazy." Like yes we are social animals... but is our performance in a social setting really our personality? It just seems like a weird externalised sort of way of describing the "essence" of a person.

This has to do with what I mentioned earlier in this post about how some questions can be indicators of a trait but not explicitly be about personality. By framing questions in specific situational or behavioral contexts, subjects can more easily understand what is being asked. These types of questions also tend to have high correlations with the primary five traits. The drawback is the more situationally dependent your question is, the more vulnerable it is to irrelevant cultural or conditional understandings. For example, I might have a messy room but an immaculate desk. Asking only about the room or desk would bias your results. Further, asking about how often you go out to bars will only make sense within a culture. In america, this could be a good measure of extroversion, but in cultures where drinking is less central to socializing (like china) would not have that same result.

I don't feel any enthusiasm about this theory. It seems very oriented in commercial philosophies, job selection testing. That approach to hiring, which is so pervasive right now, eg "It's not what you know it's who you know", "Show your passion", "It's important to get the right person", "You need to develop your soft skills", really irks me. It's all just excuses for hiring managers to go with the candidate they "feel" is "the right fit" rather than the candidate who can demonstrate actual legitimate skill development and task performance.

MBTI has its many flaws... but by comparison in its potential commercial application, it's much more oriented towards being like actually useful to the job seeker. "Check out these careers that have been of interest to people you have something in common with!"

I don't completely understand the first paragraph here, but I can tell you that MBTI fails to predict any job success, but conscientiousness is an excellent indicator of job success. While MBTI was designed as a way to match people with careers and jobs, it was completely unfounded in science, and it has failed to reflect the data. In fact, MBTI fails to successfully divide more than 80% of the population into any of the 16 types. However, the big five, by its very design, can describe everyone. It may not give the same detail in predictions as MBTI, but the big five does provide accurate predictions across the entire population.

. Maybe I can help answer some of these questions

. Maybe I can help answer some of these questions