You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Merkabah

- Thread starter Skarekrow

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

A good first hand account....not too dissimilar from some of my own.

Sleep paralysis cannot account for objects moving either, lol.

Thoughts?

Enjoy!

I thought I would share with you one of my very own strange encounters of the dream-based type.

It all went down on February 8, 2016.

Something came calling.

The day was a very strange one.

Or, to be absolutely correct, it was a strange night.

I went to bed around midnight, and, at roughly 2:00 a.m., I was semi-woken up by the sounds of what began as unintelligible, disembodied mumbling.

They appeared to be coming from something lurking in the shadows of the darkened hallway that links my bedroom to my living-room.

I then heard something speak to me in a deep, gravelly, and hoarse whisper that was not at all unintelligible: “I can help you. Just say ‘yes,’” it said.

The skeptics would almost certainly say that what I experienced was a bout of so-called sleep paralysis – a condition which can result in an inability to move, and a sense of intense and impending danger in the bedroom.

I don’t doubt that’s what it was.

But, where I differ from the skeptics is that, unlike them, I believe sleep paralysis has an external, rather than an internal origin.

Indeed, I have a number of cases where both husband and wife were semi-woken – simultaneously – by strange creatures and in situations that yet again many might write-off as just the misfiring of the brain.

We’re talking about dream-invaders of just about the vilest kind possible.

Even in my partially-asleep state I knew there was nothing but dangerous deception and manipulation at work.

I said out loud “No,” and focused on putting a barrier between me and it.

Whatever it actually was.

I got a distinct and disturbing feeling that had I said “Yes,” I would have given the unearthly thing permission to invade my space and wreak god knows what kinds of havoc and mayhem.

I also got the feeling that the thing was massively pissed by my negative response.

In light of the “dream invasion” of the early hours of February 8, I spent a great deal of the 9th to the 11th researching, and pondering on, the means by which supernatural entities may be able to invade and take control of our dream states.

One of the people whose studies I focused upon was Samuel Hatfield, a mystic and energetic healer.

I have to say that, as I read Hatfield’s words, I could not deny this sounded eerily like much of the weirdness I experienced.

And, for no less than two more nights, similar occurrences took place.

On these occasions, however, the voices were always unintelligible.

All I could tell for sure was that words were being spoken – in a rapid-fire, almost wildly mad, fashion.

But, what those words were, I had no idea.

I still don’t know.

Then, suddenly, the dream-invaders were no more.

Perhaps my reluctance to do their bidding led them to turn their evil attentions elsewhere and target some other soul or several.

Sleep paralysis cannot account for objects moving either, lol.

Thoughts?

Enjoy!

I thought I would share with you one of my very own strange encounters of the dream-based type.

It all went down on February 8, 2016.

Something came calling.

The day was a very strange one.

Or, to be absolutely correct, it was a strange night.

I went to bed around midnight, and, at roughly 2:00 a.m., I was semi-woken up by the sounds of what began as unintelligible, disembodied mumbling.

They appeared to be coming from something lurking in the shadows of the darkened hallway that links my bedroom to my living-room.

I then heard something speak to me in a deep, gravelly, and hoarse whisper that was not at all unintelligible: “I can help you. Just say ‘yes,’” it said.

The skeptics would almost certainly say that what I experienced was a bout of so-called sleep paralysis – a condition which can result in an inability to move, and a sense of intense and impending danger in the bedroom.

I don’t doubt that’s what it was.

But, where I differ from the skeptics is that, unlike them, I believe sleep paralysis has an external, rather than an internal origin.

Indeed, I have a number of cases where both husband and wife were semi-woken – simultaneously – by strange creatures and in situations that yet again many might write-off as just the misfiring of the brain.

We’re talking about dream-invaders of just about the vilest kind possible.

Even in my partially-asleep state I knew there was nothing but dangerous deception and manipulation at work.

I said out loud “No,” and focused on putting a barrier between me and it.

Whatever it actually was.

I got a distinct and disturbing feeling that had I said “Yes,” I would have given the unearthly thing permission to invade my space and wreak god knows what kinds of havoc and mayhem.

I also got the feeling that the thing was massively pissed by my negative response.

In light of the “dream invasion” of the early hours of February 8, I spent a great deal of the 9th to the 11th researching, and pondering on, the means by which supernatural entities may be able to invade and take control of our dream states.

One of the people whose studies I focused upon was Samuel Hatfield, a mystic and energetic healer.

In his own very insightful words:

“Why would someone purposefully invade someone else’s dream?

Well, there are a number of reasons; the chief among them is to influence someone’s thinking.

Much of what occurs in a dream is left in the subconscious or unconscious mind.

The subconscious / unconscious mind influences much of our daily lives.

It governs the automatic responses and processes such as memory, motivation, instinct, and even emotional reaction. Purposeful invaders often seek to influence these things to invoke particular responses in others.

They do this by entering the lucid dream,

or even pulling someone into their own dream and implanting thought forms to condition the subject.”

“Why would someone purposefully invade someone else’s dream?

Well, there are a number of reasons; the chief among them is to influence someone’s thinking.

Much of what occurs in a dream is left in the subconscious or unconscious mind.

The subconscious / unconscious mind influences much of our daily lives.

It governs the automatic responses and processes such as memory, motivation, instinct, and even emotional reaction. Purposeful invaders often seek to influence these things to invoke particular responses in others.

They do this by entering the lucid dream,

or even pulling someone into their own dream and implanting thought forms to condition the subject.”

I have to say that, as I read Hatfield’s words, I could not deny this sounded eerily like much of the weirdness I experienced.

And, for no less than two more nights, similar occurrences took place.

On these occasions, however, the voices were always unintelligible.

All I could tell for sure was that words were being spoken – in a rapid-fire, almost wildly mad, fashion.

But, what those words were, I had no idea.

I still don’t know.

Then, suddenly, the dream-invaders were no more.

Perhaps my reluctance to do their bidding led them to turn their evil attentions elsewhere and target some other soul or several.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Good morning!

A fascinating subject!

Do you agree with the conclusions?

:<3white:

Does quantum mechanics predict the existence of a spiritual “soul”?

Testimonials from prominent physics researchers from institutions such as Cambridge University, Princeton University, and the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich claim that quantum mechanicspredicts some version of “life after death.”

They assert that a person may possess a body-soul duality that is an extension of the wave-particle duality of subatomic particles.

Wave-particle duality, a fundamental concept of quantum mechanics, proposes that elementary particles, such as photons and electrons, possess the properties of both particles and waves.

These physicists claim that they can possibly extend this theory to the soul-body dichotomy.

If there is a quantum code for all things, living and dead, then there is an existence after death (speaking in purely physical terms).

Dr. Hans-Peter Dürr, former head of the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich, posits that, just as a particle “writes” all of its information on its wave function, the brain is the tangible “floppy disk” on which we save our data, and this data is then “uploaded” into the spiritual quantum field.

Continuing with this analogy, when we die the body, or the physical disk, is gone, but our consciousness, or the data on the computer, lives on.

“What we consider the here and now, this world, it is actually just the material level that is comprehensible. The beyond is an infinite reality that is much bigger. Which this world is rooted in. In this way, our lives in this plane of existence are encompassed, surrounded, by the afterworld already… The body dies but the spiritual quantum field continues. In this way, I am immortal,” says Dürr.

Dr. Christian Hellwig of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, found evidence that information in our central nervous system is phase encoded, a type of coding that allows multiple pieces of data to occupy the same time.

He said, “Our thoughts, our will, our consciousness and our feelings show properties that could be referred to as spiritual properties…No direct interaction with the known fundamental forces of natural science, such as gravitation, electromagnetic forces, etc. can be detected in the spiritual. On the other hand, however, these spiritual properties correspond exactly to the characteristics that distinguish the extremely puzzling and wondrous phenomena in the quantum world.”

Physicist Professor Robert Jahn of Princeton University concluded that if consciousness can exchange information in both directions with the physical environment, then it can be attributed with the same “molecular binding potential” as physical objects, meaning that it must also follow the tenets of quantum mechanics.

Quantum physicist David Bohm, a student and friend of Albert Einstein, was of a similar opinion.

He stated, “The results of modern natural sciences only make sense if we assume an inner, uniform, transcendent reality that is based on all external data and facts. The very depth of human consciousness is one of them.”

A fascinating subject!

Do you agree with the conclusions?

:<3white:

The Soul and Quantum Physics

I knew the time would soon come when physicists would tackle the survival after physical life question.

This article represents an important early step.

Written by Janey Tracey in June 17, 2014, and published online at Outer Places.

Physicists Claim that Consciousness Lives

in Quantum State After Death

I knew the time would soon come when physicists would tackle the survival after physical life question.

This article represents an important early step.

Written by Janey Tracey in June 17, 2014, and published online at Outer Places.

Physicists Claim that Consciousness Lives

in Quantum State After Death

Does quantum mechanics predict the existence of a spiritual “soul”?

Testimonials from prominent physics researchers from institutions such as Cambridge University, Princeton University, and the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich claim that quantum mechanicspredicts some version of “life after death.”

They assert that a person may possess a body-soul duality that is an extension of the wave-particle duality of subatomic particles.

Wave-particle duality, a fundamental concept of quantum mechanics, proposes that elementary particles, such as photons and electrons, possess the properties of both particles and waves.

These physicists claim that they can possibly extend this theory to the soul-body dichotomy.

If there is a quantum code for all things, living and dead, then there is an existence after death (speaking in purely physical terms).

Dr. Hans-Peter Dürr, former head of the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich, posits that, just as a particle “writes” all of its information on its wave function, the brain is the tangible “floppy disk” on which we save our data, and this data is then “uploaded” into the spiritual quantum field.

Continuing with this analogy, when we die the body, or the physical disk, is gone, but our consciousness, or the data on the computer, lives on.

“What we consider the here and now, this world, it is actually just the material level that is comprehensible. The beyond is an infinite reality that is much bigger. Which this world is rooted in. In this way, our lives in this plane of existence are encompassed, surrounded, by the afterworld already… The body dies but the spiritual quantum field continues. In this way, I am immortal,” says Dürr.

Dr. Christian Hellwig of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, found evidence that information in our central nervous system is phase encoded, a type of coding that allows multiple pieces of data to occupy the same time.

He said, “Our thoughts, our will, our consciousness and our feelings show properties that could be referred to as spiritual properties…No direct interaction with the known fundamental forces of natural science, such as gravitation, electromagnetic forces, etc. can be detected in the spiritual. On the other hand, however, these spiritual properties correspond exactly to the characteristics that distinguish the extremely puzzling and wondrous phenomena in the quantum world.”

Physicist Professor Robert Jahn of Princeton University concluded that if consciousness can exchange information in both directions with the physical environment, then it can be attributed with the same “molecular binding potential” as physical objects, meaning that it must also follow the tenets of quantum mechanics.

Quantum physicist David Bohm, a student and friend of Albert Einstein, was of a similar opinion.

He stated, “The results of modern natural sciences only make sense if we assume an inner, uniform, transcendent reality that is based on all external data and facts. The very depth of human consciousness is one of them.”

John K

Donor

- MBTI

- INFJ

- Enneagram

- 5W4 549

At the broadest level this just seems to me to be stating the obvious. I'm agnostic on the actual details they suggest because quantum mechanics by itself doesn't model all of reality as we experience it. What does seem obvious is that conscious is as much a property of reality as anything else, not some bolted on epiphenomenum; and that the substance of reality is more like software than solid stuff, so consciousness and the material of our world must be a lot closer to each other in their character than seems obvious to the senses.Good morning!

A fascinating subject!

Do you agree with the conclusions?

:<3white:

The Soul and Quantum Physics

I knew the time would soon come when physicists would tackle the survival after physical life question.

This article represents an important early step.

Written by Janey Tracey in June 17, 2014, and published online at Outer Places.

Physicists Claim that Consciousness Lives

in Quantum State After Death

Does quantum mechanics predict the existence of a spiritual “soul”?

Testimonials from prominent physics researchers from institutions such as Cambridge University, Princeton University, and the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich claim that quantum mechanicspredicts some version of “life after death.”

They assert that a person may possess a body-soul duality that is an extension of the wave-particle duality of subatomic particles.

Wave-particle duality, a fundamental concept of quantum mechanics, proposes that elementary particles, such as photons and electrons, possess the properties of both particles and waves.

These physicists claim that they can possibly extend this theory to the soul-body dichotomy.

If there is a quantum code for all things, living and dead, then there is an existence after death (speaking in purely physical terms).

Dr. Hans-Peter Dürr, former head of the Max Planck Institute for Physics in Munich, posits that, just as a particle “writes” all of its information on its wave function, the brain is the tangible “floppy disk” on which we save our data, and this data is then “uploaded” into the spiritual quantum field.

Continuing with this analogy, when we die the body, or the physical disk, is gone, but our consciousness, or the data on the computer, lives on.

“What we consider the here and now, this world, it is actually just the material level that is comprehensible. The beyond is an infinite reality that is much bigger. Which this world is rooted in. In this way, our lives in this plane of existence are encompassed, surrounded, by the afterworld already… The body dies but the spiritual quantum field continues. In this way, I am immortal,” says Dürr.

Dr. Christian Hellwig of the Max Planck Institute for Biophysical Chemistry in Göttingen, found evidence that information in our central nervous system is phase encoded, a type of coding that allows multiple pieces of data to occupy the same time.

He said, “Our thoughts, our will, our consciousness and our feelings show properties that could be referred to as spiritual properties…No direct interaction with the known fundamental forces of natural science, such as gravitation, electromagnetic forces, etc. can be detected in the spiritual. On the other hand, however, these spiritual properties correspond exactly to the characteristics that distinguish the extremely puzzling and wondrous phenomena in the quantum world.”

Physicist Professor Robert Jahn of Princeton University concluded that if consciousness can exchange information in both directions with the physical environment, then it can be attributed with the same “molecular binding potential” as physical objects, meaning that it must also follow the tenets of quantum mechanics.

Quantum physicist David Bohm, a student and friend of Albert Einstein, was of a similar opinion.

He stated, “The results of modern natural sciences only make sense if we assume an inner, uniform, transcendent reality that is based on all external data and facts. The very depth of human consciousness is one of them.”

Quantum indeterminacy is a strange thing - there is a very small but finite chance that a proton in one of the atoms in my fingernail could instantaneously transfer into orbit around the star Betelgeuse. There is a hugely higher probability that it will firmly stay put inside the carbon atom in your nail so it stays there. Suppose though that some catastrophe of time and space eliminated all the other more likely possibilities - then to Betelgeuse it will go. So suppose when we die the same quantum laws apply and that there is an incredibly small but finite possibility of our consciousness transferring to another host, maybe elsewhere in time or space, or maybe in a different reality - there is nowhere else for it to go so that's where it ends up, and we survive.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

At the broadest level this just seems to me to be stating the obvious. I'm agnostic on the actual details they suggest because quantum mechanics by itself doesn't model all of reality as we experience it. What does seem obvious is that conscious is as much a property of reality as anything else, not some bolted on epiphenomenum; and that the substance of reality is more like software than solid stuff, so consciousness and the material of our world must be a lot closer to each other in their character than seems obvious to the senses.

Quantum indeterminacy is a strange thing - there is a very small but finite chance that a proton in one of the atoms in my fingernail could instantaneously transfer into orbit around the star Betelgeuse. There is a hugely higher probability that it will firmly stay put inside the carbon atom in your nail so it stays there. Suppose though that some catastrophe of time and space eliminated all the other more likely possibilities - then to Betelgeuse it will go. So suppose when we die the same quantum laws apply and that there is an incredibly small but finite possibility of our consciousness transferring to another host, maybe elsewhere in time or space, or maybe in a different reality - there is nowhere else for it to go so that's where it ends up, and we survive.

I agree John!

It’s pretty obvious to some...there are still others who will find it new and it starts them down a pathway to new discoveries.

If you ever wake up with a tiny hole in your fingernail you’ll know where it went!!

lol

I can say from my own perspective that I think there is something beyond death...there are the known unknowns and unknown knowns.

As Slavoj Žižek said - The things we know, but are unaware of knowing...lol.

Which is a whole lot of stuff if you ask me.

Most people don’t ever really take the time to even understand how their body functions (anatomy/physiology being a familiar subject), even though it is the thing that allows us to exist in this reality and physically move and do everything else.

Such as your heart...it beats approx. 100,000 times every day...no break...no rest.

That’s 35 million times in a lifetime - there is no machine as complex made by mankind that could last even a fraction of that (especially one with moving parts).

People think a human heart is squishy...not so...it’s like feeling a flexed bicep or other muscle...and that’s in a state of rest it’s so damn buff!!

It was strange the first time I held one to retract it out of the way...so incredible.

Not to mention we always have “cancerous" cells in our body all the time...all of us, (in quotations because they are potentially cancer causing) but our body and immune system keep them in check for the most part until there is a breakdown of some kind or certain cells evolve.

Even the “malfunction” I have to deal with concerning the ankylosing spondylitis is fascinating to me as someone who has always loved medical science and the sciences in general.

I remember checking out books on Neurochemistry from the public library around age 12 and just devouring them though I still was missing parts of the knowledge that went over my head in the book - as there was no internet at that time to reference big latin words, lol.

What I did understand, I wanted more of...and I had it in my head to somehow work with neurochemistry for many years.

(Got so far as assisting with Neurosurgery so - close enough!)

I even wrote a short and probably not very convincing proposal on the possibility that the visions of Nirvana or enlightenment that certain individuals would see after years and years of meditation practice - could in actuality be a trained, natural overdose of certain neurotransmitters causing a self-induced psychedelic trip of sorts.

This would naturally be interpreted by those with no practical knowledge of the brain to conclude it was something more fantastical that it really was - though a self-induced trip is still fantastic!

Anyhow...you would have to have some way to measure the specific chemistry and probably want an fMRI to make some sort of further extrapolation, lol.

Sorry to hear that you have been sick!

Lots of good positive energy coming your way!!

That is terrible sounding stuff...take it easy and don’t skip the doctor if it keeps on!

:<3white:

I was sicker than a dog yesterday....but it was strange.

I woke up, felt fine...then about 20 mins later I felt like I was flushed and gonna puke...was sure it was a forgone conclusion hahaha.

I did not thank goodness...but the whole rest of the morning and all afternoon I felt nauseous and had no appetite...kept alternating between burning up and sweating, and freezing...so there could have been some fever, idk since I have no thermometer, dur.

Then about 5pm it all just started to subside and I felt hungry and had dinner and felt fine the rest of the night and currently!

IDK if I was fighting something off or something weird was going on in my guts...*shrug*...glad it’s gone.

My asthma has been doing stuff too like you said - I had so-so on the bad scale of childhood asthma...not as bad as some...but it has mostly gone as I’ve gotten older...except when it gets cold...which it did recently...nothing uncontrollable...just relatable to what you were saying in your thread.

Anyhow...I’ve always liked the analogy of our physical brain being the hardware and the soul or energy or whatever being the software.

The TV set analogy where you can fool around with components inside makes total sense...if you pull out this circuit the picture goes out...just as cutting certain nerves in the brain will make us blind...it doesn’t mean the signal (which I believe is probably the dark matter/energy that permeates everything around us and through us - could be pure consciousness) for the picture is not there anymore, it just has no way to be translated from the signal form it’s in now due to the disconnect or damage.

Though....what’s crazy is sometimes those with dementia or Alzheimer’s will have a few hours or a day of lucidity right before they pass even when there should be no physical way for the brain to be functional enough for them to do so...there is materially no way...and yet it happens.

So somehow it seems the physical brain can be bypassed or superseded under the right conditions...

Just like those few blind near-death experiencers who could see for the first time when they left their bodies, and they understood they could see themselves and what colors were what...one even had a brain scan...when recalling the sensation of “seeing” the occipital region of their brain lit up.

Amazing!

We know so little.

It’s very humbling to think about it all!

I just read a story I will post up here about how flowers can “hear” a bee buzzing (sense the vibrations) and will actually sweeten it’s nectar as a response to draw them in.

This was in National Geographic, not some woo-woo site either, lol.

(will put that up shortly)

That’s quite a ramble...sorry!

I hope you are doing better John...tell your body to fight the bastards!

Much love!

:<3white:

Last edited:

John K

Donor

- MBTI

- INFJ

- Enneagram

- 5W4 549

Something I found really weird when I first came across the idea is that our bodies and minds have no physical permanence. I'm not talking about anything esoteric, but just the way that we are more like a river than a mountain. Everything we are made of is constantly flowing through us. This came up recently in the forum didn't it? - the Dawkins quote about none of the physical material of our bodies being more than 10 years old and is being constantly replaced. It's like the parable of the old favourite car that starts to wear out over the years, so bit by bit all it's parts are replaced until in the end there is nothing left that was there when the car was first new. Yet it's still the same old favourite car. The shape, the pattern, is vastly more important than the physical stuff that gives it substance at any one time. The same with our bodies.Most people don’t ever really take the time to even understand how their body functions (anatomy/physiology being a familiar subject), even though it is the thing that allows us to exist in this reality and physically move and do everything else.

It all seems perfectly natural to me now of course, and a delightful part of the world and the way we exist in it. It reinforces strongly the idea that the software is the determinant, doesn't it?

Thanks SkareSorry to hear that you have been sick!

Lots of good positive energy coming your way!!

That is terrible sounding stuff...take it easy and don’t skip the doctor if it keeps on!

It was a good ramble - many thanks for itThat’s quite a ramble...sorry!

I hope you are doing better John...tell your body to fight the bastards!

Much love!

I shall follow your advice

Much love Skare!

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Something I found really weird when I first came across the idea is that our bodies and minds have no physical permanence. I'm not talking about anything esoteric, but just the way that we are more like a river than a mountain. Everything we are made of is constantly flowing through us. This came up recently in the forum didn't it? - the Dawkins quote about none of the physical material of our bodies being more than 10 years old and is being constantly replaced. It's like the parable of the old favourite car that starts to wear out over the years, so bit by bit all it's parts are replaced until in the end there is nothing left that was there when the car was first new. Yet it's still the same old favourite car. The shape, the pattern, is vastly more important than the physical stuff that gives it substance at any one time. The same with our bodies.

It all seems perfectly natural to me now of course, and a delightful part of the world and the way we exist in it. It reinforces strongly the idea that the software is the determinant, doesn't it?

Thanks Skare. I'm going to see how it goes by the end of the week and head on down there if it shows no sign of clearing up. The docs are all scared of prescribing antibiotics these days unless there is a very compelling reason, and I can work out all the other treatments for myself - I get this sort of thing at least once a year (though this is the worst I've been) so I've got the manual lol. The thing I can't put up with is the dry cough that comes with a bit of lung inflamation, triggering my asthma, so I'm taking the maximum Ventolin allowed - I normally don't use any of that, but it relaxes my breathing when I get like this. I've increased my steroid inhaler too, but I think I need to check out with the docs before doubling up on that a second time. At least I'm not working and can just chill out at home without worrying about things slipping - mind you I'd probably recover faster if I were younger.

It was a good ramble - many thanks for it

I shall follow your advice

Much love Skare!

Yes...now if we could just keep our DNA from deteriorating we could live forever!

(No thanks....)

Dry coughs suck...since you live in the UK you have access to cough syrup with codeine in it...of course we all know it can be abused as a pain reliever and mild opiate, but codeine itself supposedly decreases activity in the part of the brain that causes you to cough.

Has always worked great for me with a dry cough....besides sitting in a steamy shower and breathing it in.

When I was flying back from Moscow I stopped at London, Heathrow and was really sick...they had some medicine in one of the shops there while I waited for my flight and picked one that looked strong, lol.

I took a swig and in about 15 mins realized it had codeine in it after getting a bit light-headed and then reading the ingredients hahaha.

They must put something in it to keep people from abusing it though cause it tasted like bitter gasoline (not that I know)!

I actually threw the rest away when I got home despite it only being by prescription here since it tasted sooooo foul.

Maybe you know the brand...it was some old timey fancy label....oh god it was hard to drink.

Still - it worked!

For the flight back to the states it kept me from coughing all over my seat mates.

Take care!

PS - The albuterol inhaler will actually contribute to drying out the cough...so the more time between puffs the better in that regard.

Last edited:

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Intelligence can be found in the most overlooked places.

That it could learn and adapt gives you a whole new perspective.

Nature is simply incredible!

Thoughts?

Enjoy!

( @John K - here is that article)

Even on the quietest days, the world is full of sounds: birds chirping, wind rustling through trees, and insects humming about their business.

The ears of both predator and prey are attuned to one another’s presence.

Sound is so elemental to life and survival that it prompted Tel Aviv University researcher Lilach Hadany to ask: What if it wasn’t just animals that could sense sound—what if plants could, too?

The first experiments to test this hypothesis, published recently on the pre-print server bioRxiv, suggest that in at least one case, plants can hear, and it confers a real evolutionary advantage.

Hadany’s team looked at evening primroses (Oenothera drummondii) and found that within minutes of sensing vibrations from pollinators’ wings, the plants temporarily increased the concentration of sugar in their flowers’ nectar.

In effect, the flowers themselves served as ears, picking up the specific frequencies of bees’ wings while tuning out irrelevant sounds like wind.

The sweetest sound

As an evolutionary theoretician, Hadany says her question was prompted by the realization that sounds are a ubiquitous natural resource—one that plants would be wasting if they didn’t take advantage of it as animals do.

If plants had a way of hearing and responding to sound, she figured, it could help them survive and pass on their genetic legacy.

Since pollination is key to plant reproduction, her team started by investigating flowers.

Evening primrose, which grows wild on the beaches and in parks around Tel Aviv, emerged as a good candidate, since it has a long bloom time and produces measurable quantities of nectar.

To test the primroses in the lab, Hadany’s team exposed plants to five sound treatments: silence, recordings of a honeybee from four inches away, and computer-generated sounds in low, intermediate, and high frequencies.

Plants given the silent treatment—placed under vibration-blocking glass jars—had no significant increase in nectar sugar concentration.

The same went for plants exposed to high-frequency (158 to 160 kilohertz) and intermediate-frequency (34 to 35 kilohertz) sounds.

But for plants exposed to playbacks of bee sounds (0.2 to 0.5 kilohertz) and similarly low-frequency sounds (0.05 to 1 kilohertz), the final analysis revealed an unmistakable response.

Within three minutes of exposure to these recordings, sugar concentration in the plants increased from between 12 and 17 percent to 20 percent.

A sweeter treat for pollinators, their theory goes, may draw in more insects, potentially increasing the chances of successful cross-pollination.

Indeed, in field observations, researchers found that pollinators were more than nine times more common around plants another pollinator had visited within the previous six minutes.

“We were quite surprised when we found out that it actually worked,” Hadany says. “But after repeating it in other situations, in different seasons, and with plants grown both indoors and outdoors, we feel very confident in the result.”

Flowers for ears

As the team thought about how sound works, via the transmission and interpretation of vibrations, the role of the flowers became even more intriguing. Though blossoms vary widely in shape and size, a good many are concave or bowl-shaped.

This makes them perfect for receiving and amplifying sound waves, much like a satellite dish.

To test the vibrational effects of each sound frequency test group, Hadany and her co-author Marine Veits, then a graduate student in Hadany’s lab, put the evening primrose flowers under a machine called a laser vibrometer, which measures minute movements.

The team then compared the flowers’ vibrations with those from each of the sound treatments.

“This specific flower is bowl- shaped, so acoustically speaking, it makes sense that this kind of structure would vibrate and increase the vibration within itself,” Veits says.

And indeed it did, at least for the pollinators’ frequencies.

Hadany says it was exciting to see the vibrations of the flower match up with the wavelengths of the bee recording.

“You immediately see that it works,” she says.

To confirm that the flower was the responsible structure, the team also ran tests on flowers that had one or more petals removed.

Those flowers failed to resonate with either of the low-frequency sounds.

What else plants can hear

Hadany acknowledges that there are many, many questions remaining about this newfound ability of plants to respond to sound.

Are some “ears” better for certain frequencies than others?

And why does the evening primrose make its nectar so much sweeter when bees are known to be able to detect changes in sugar concentration as small as 1 to 3 percent?

Also, could this ability confer other advantages beyond nectar production and pollination?

Hadany posits that perhaps plants alert one another to the sound of herbivores mowing down their neighbors.

Or maybe they can generate sounds that attract the animals involved in dispersing that plant’s seeds.

“We have to take into account that flowers have evolved with pollinators for a very long time,” Hadany says. “They are living entities, and they, too, need to survive in the world. It’s important for them to be able to sense their environment—especially if they cannot go anywhere.”

This single study has cracked open an entirely new field of scientific research, which Hadany calls phytoacoustics.

Veits wants to know more about the underlying mechanisms behind the phenomenon the research team observed.

For instance, what molecular or mechanical processes are driving the vibration and nectar response?

She also hopes the work will affirm the idea that it doesn’t always take a traditional sense organ to perceive the world.

“Some people may think, How can [plants] hear or smell?” Veits says. “I’d like people to understand that hearing is not only for ears.”

Richard Karban, an expert in interactions between plants and their pests at the University of California Davis, has questions of his own, in particular, about the evolutionary advantages of plants’ responses to sound.

“It may be possible that plants are able to chemically sense their neighbors, and to evaluate whether or not other plants around them are fertilized,” he says. “There’s no evidence that things like that are going on, but [this study] has done the first step.”

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct the percent increase in nectar's sugar concentration.

That it could learn and adapt gives you a whole new perspective.

Nature is simply incredible!

Thoughts?

Enjoy!

( @John K - here is that article)

Flowers can hear buzzing bees—and it makes their nectar sweeter

“I’d like people to understand that hearing is not only for ears.”

BY MICHELLE Z. DONAHUE

The bowl-shaped flowers of evening primrose may be key to their acoustic capabilities.

“I’d like people to understand that hearing is not only for ears.”

BY MICHELLE Z. DONAHUE

The bowl-shaped flowers of evening primrose may be key to their acoustic capabilities.

Even on the quietest days, the world is full of sounds: birds chirping, wind rustling through trees, and insects humming about their business.

The ears of both predator and prey are attuned to one another’s presence.

Sound is so elemental to life and survival that it prompted Tel Aviv University researcher Lilach Hadany to ask: What if it wasn’t just animals that could sense sound—what if plants could, too?

The first experiments to test this hypothesis, published recently on the pre-print server bioRxiv, suggest that in at least one case, plants can hear, and it confers a real evolutionary advantage.

Hadany’s team looked at evening primroses (Oenothera drummondii) and found that within minutes of sensing vibrations from pollinators’ wings, the plants temporarily increased the concentration of sugar in their flowers’ nectar.

In effect, the flowers themselves served as ears, picking up the specific frequencies of bees’ wings while tuning out irrelevant sounds like wind.

The sweetest sound

As an evolutionary theoretician, Hadany says her question was prompted by the realization that sounds are a ubiquitous natural resource—one that plants would be wasting if they didn’t take advantage of it as animals do.

If plants had a way of hearing and responding to sound, she figured, it could help them survive and pass on their genetic legacy.

Since pollination is key to plant reproduction, her team started by investigating flowers.

Evening primrose, which grows wild on the beaches and in parks around Tel Aviv, emerged as a good candidate, since it has a long bloom time and produces measurable quantities of nectar.

To test the primroses in the lab, Hadany’s team exposed plants to five sound treatments: silence, recordings of a honeybee from four inches away, and computer-generated sounds in low, intermediate, and high frequencies.

Plants given the silent treatment—placed under vibration-blocking glass jars—had no significant increase in nectar sugar concentration.

The same went for plants exposed to high-frequency (158 to 160 kilohertz) and intermediate-frequency (34 to 35 kilohertz) sounds.

But for plants exposed to playbacks of bee sounds (0.2 to 0.5 kilohertz) and similarly low-frequency sounds (0.05 to 1 kilohertz), the final analysis revealed an unmistakable response.

Within three minutes of exposure to these recordings, sugar concentration in the plants increased from between 12 and 17 percent to 20 percent.

A sweeter treat for pollinators, their theory goes, may draw in more insects, potentially increasing the chances of successful cross-pollination.

Indeed, in field observations, researchers found that pollinators were more than nine times more common around plants another pollinator had visited within the previous six minutes.

“We were quite surprised when we found out that it actually worked,” Hadany says. “But after repeating it in other situations, in different seasons, and with plants grown both indoors and outdoors, we feel very confident in the result.”

Flowers for ears

As the team thought about how sound works, via the transmission and interpretation of vibrations, the role of the flowers became even more intriguing. Though blossoms vary widely in shape and size, a good many are concave or bowl-shaped.

This makes them perfect for receiving and amplifying sound waves, much like a satellite dish.

To test the vibrational effects of each sound frequency test group, Hadany and her co-author Marine Veits, then a graduate student in Hadany’s lab, put the evening primrose flowers under a machine called a laser vibrometer, which measures minute movements.

The team then compared the flowers’ vibrations with those from each of the sound treatments.

“This specific flower is bowl- shaped, so acoustically speaking, it makes sense that this kind of structure would vibrate and increase the vibration within itself,” Veits says.

And indeed it did, at least for the pollinators’ frequencies.

Hadany says it was exciting to see the vibrations of the flower match up with the wavelengths of the bee recording.

“You immediately see that it works,” she says.

To confirm that the flower was the responsible structure, the team also ran tests on flowers that had one or more petals removed.

Those flowers failed to resonate with either of the low-frequency sounds.

What else plants can hear

Hadany acknowledges that there are many, many questions remaining about this newfound ability of plants to respond to sound.

Are some “ears” better for certain frequencies than others?

And why does the evening primrose make its nectar so much sweeter when bees are known to be able to detect changes in sugar concentration as small as 1 to 3 percent?

Also, could this ability confer other advantages beyond nectar production and pollination?

Hadany posits that perhaps plants alert one another to the sound of herbivores mowing down their neighbors.

Or maybe they can generate sounds that attract the animals involved in dispersing that plant’s seeds.

“We have to take into account that flowers have evolved with pollinators for a very long time,” Hadany says. “They are living entities, and they, too, need to survive in the world. It’s important for them to be able to sense their environment—especially if they cannot go anywhere.”

This single study has cracked open an entirely new field of scientific research, which Hadany calls phytoacoustics.

Veits wants to know more about the underlying mechanisms behind the phenomenon the research team observed.

For instance, what molecular or mechanical processes are driving the vibration and nectar response?

She also hopes the work will affirm the idea that it doesn’t always take a traditional sense organ to perceive the world.

“Some people may think, How can [plants] hear or smell?” Veits says. “I’d like people to understand that hearing is not only for ears.”

Richard Karban, an expert in interactions between plants and their pests at the University of California Davis, has questions of his own, in particular, about the evolutionary advantages of plants’ responses to sound.

“It may be possible that plants are able to chemically sense their neighbors, and to evaluate whether or not other plants around them are fertilized,” he says. “There’s no evidence that things like that are going on, but [this study] has done the first step.”

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to correct the percent increase in nectar's sugar concentration.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

I really love these kinds of studies!

I’ve heard a lot of stories from very credible Nurses, Doctors, and Surgeons over the years as well as seeing it with my own eyes.

Most of them will tell there is a moment when you can see the soul leave...it’s pretty noticeable after you’ve witnessed a lot of people passing.

You can have two identical patients who are clinically dead and the doctor will continue CPR and live saving measures sometimes for a loooong time on one...and then you will have another patient where you can see the soul is missing or has left or you see it go...it’s not explainable other than there is just this change that occurs with them, and CPR will be halted, time of death called.

No visible apparitions or anything, but the life-force is gone and somehow we can sense that if in tune...idk...ask a RN and see!

I feel I have been very blessed to witness the passing of many souls...when it’s your time - no amount of medical intervention will get in the way.

Sorry to be so morbid!!!

Enjoy!

:<3white:

I’ve heard a lot of stories from very credible Nurses, Doctors, and Surgeons over the years as well as seeing it with my own eyes.

Most of them will tell there is a moment when you can see the soul leave...it’s pretty noticeable after you’ve witnessed a lot of people passing.

You can have two identical patients who are clinically dead and the doctor will continue CPR and live saving measures sometimes for a loooong time on one...and then you will have another patient where you can see the soul is missing or has left or you see it go...it’s not explainable other than there is just this change that occurs with them, and CPR will be halted, time of death called.

No visible apparitions or anything, but the life-force is gone and somehow we can sense that if in tune...idk...ask a RN and see!

I feel I have been very blessed to witness the passing of many souls...when it’s your time - no amount of medical intervention will get in the way.

Sorry to be so morbid!!!

Enjoy!

:<3white:

Brief Research:

A Follow-Up Study on

Unusual Perceptual Experiences in Hospital Settings Related by Nurses

ALEJANDRO PARRA

Instituto de Psicología Paranormal rapp@fibertel.com.ar

Submitted March 4, 2018; Accepted June 3, 2018; Published December 31, 2018

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31275/2018.1310Copyright: Creative Commons CC-BY-NC

A Follow-Up Study on

Unusual Perceptual Experiences in Hospital Settings Related by Nurses

ALEJANDRO PARRA

Instituto de Psicología Paranormal rapp@fibertel.com.ar

Submitted March 4, 2018; Accepted June 3, 2018; Published December 31, 2018

DOI: https://doi.org/10.31275/2018.1310Copyright: Creative Commons CC-BY-NC

Abstract —The aim of this study was to determine the degree of occur- rence of certain unusual perceptual experiences in hospital settings often related by nurses, in a follow-up study at 36 hospitals and health centers in Buenos Aires.

344 nurses were grouped as 235 experiencers and 109 non- experiencers.

The most common experiences are sense of presence and/or apparitions, hearing noises, voices or dialogues, crying or complaining, and intuitions and extrasensory experiences as listeners of the experiences of their patients, such as near-death experiences, religious interventions, and many anomalous experiences in relation with children (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017).

Introduction

It is important to note that the findings related to anomalous experiences by nurses (Barbato et al. 1999, O’Connor 2003) have also been reported by doctors (Osis & Haraldsson 1977, 1997) and other caregivers in hospital settings (Brayne, Farnham, & Fenwick 2006, Katz & Payne 2003, Kellehear 2003, Fenwick & Fenwick 2008), and in care homes (Katz & Payne 2003) around a number of anomalous events such as deathbed visions (Barret 1926, Betty 2006, Brayne, Farnham, & Fenwick 2006, Brayne, Lovelace, & Fenwick 2006).

A previous, up-to-date study on anomalous experiences in hospital settings (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017), recruited nurses (n = 100) who reported a number of anomalous experiences from one health center in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Four potential traits that could “modulate” anomalous experiences in nurses are work stress, hallucination proneness, heightened attentional capacities (psychological absorption) associated with a number of anomalous experiences, and “openness” to such experiences.

It could be argued that the psychological pressure of the working conditions of nurses triggers such anomalous perceptual experiences, but a comparison between nurse experiencers and a control group in terms of work stress (i.e. nurses who reported these experiences tended to experience greater work- related stress) was not confirmed (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017).

Parra and Giménez Amarilla (2017) also found that those who reported a combination of unusual perceptual experiences and a high level of psychological absorption—a state of heightened imaginative involvement in which an individual’s attentional capacities are focused in one behavioral domain (Tellegen & Atkinson 1974)—tended to score higher for anomalous experiences compared with those who did not report such experiences.

In fact, a better predictor than work stress and hallucination-proneness was psychological absorption in experiencers compared with the control group (Parra 2015, Parra & Argibay 2012).

Of the 100 nurses they surveyed, 61 of them reported having had at least one anomalous experience in a hospital setting, the most common feelings reported were a sense of “presence” (30%), hearing noises and finding no source (17%), and knowing intuitively what was wrong with a patient without knowing their medical history (14%), patients with near-death experiences (19%), patients recovering quickly and completely from disease after religious intervention (e.g., prayer group) (18%), and anomalous experiences where children were involved (15%).

The present study represents a replication utilizing a larger number of nurses from a wider range of hospitals and health centers in Buenos Aires.

The main aim was to determine frequency and percentage of anomalous experiences across multiple hospital/health centers instead of from just one.

Methods

Participants

A total of 450 questionnaires were sent to nurses in 36 different hospitals and health service departments.

Of these, 344 (76%) usable questionnaires were returned.

The nurse participants were recruited with the cooperation of their Research and Teaching areas of the Nursing Department of each (the Principal Nursing Officers).

They gave us permission to administer the set of questionnaires, which were distributed through the Nursing Officers to each nurse in the hospital, depending on the number of nurses working in each hospital and health center (Mean = 100; Rank = 5 to 300 per hospital approximately).

The Nursing Officers verbally explained the research to each nurse on all shifts.

The Nursing Officers were also contacted through announcements in hospitals and the Internet (briefly stating the main aims of the research), and many nurses interested in spiritual/paranormal topics contacted the Nursing Officers in their hospital, some of whom also showed interest in the topic.

Another group of Nursing Officers also was contacted by the researcher who briefly stated the main aims of the study, but no hypothesis was given to the nurses employed in the hospitals.

All nurses completed the questionnaires in isolation and they returned them at the same time (the time to complete the set of questions was forty minutes).

Some nurses (n = 80) were also recruited from courses and seminars through nursing schools and health centers seminars, where the questionnaires were completed in a classroom setting with the permission of their teachers and directors.

Consent Form

The set of questionnaires included a consent form.

The nurse participants were informed that we were recruiting information on anomalous and/or spiritual experiences and they signed an appropriate consent form.

They all received significant information about the procedure and were free to decline to participate.

All data collected were treated confidentially.

Categorization Procedure

The following criteria were used to split the sample into two groups: Nurses who indicated “one time” and/or “multiples times” for (at least) one of the 13 items were categorized as the Nurse Experiencers “NEs” group (n = 235), and Nurses who indicated “never” for all 13 items were categorized as the “Control” group (n = 109).

Eight items of the Anomalous Experiences in Nurse & Health Workers Survey were used to create an Index of total experiences, that is, nurses as anomalous experiencers themselves, but nurses as listeners of the experiences from patients and other nurses were excluded (five items).

Participants

Nurse experiencers (NE).

The sample consisted of 235 nurses, of which 183 (78%) were female and 52 (22%) were male.

The age range was 19 to 68 years (Mean = 39.19 years; SD = 11.15 years).

Nurses scored a mean of 11 years in their work in hospitals (Range = 1 to 48 years; SD = 10.52).

39 (16.6%) of them worked a morning shift, 51 (21.7 %) an afternoon shift, and 45 (19.1%) the night shift (just 6 work in two shifts, 2.6%).

66 (31.8%) worked in other shift modes such as continuous shift (37, 15.7%) and weekend shift (29, 12.3%), and 28 did not mention the shift (11.9%). The main work areas surveyed were patient rooms (24.3%), guard station (13.2%), intensive care ward (22.1%), neonatology (7.7%), others (22.2%, i.e. ambulances, surgery, etc.), and undefined by the respondent (8.9%).

Nurse controls, nonexperiencer nurses (NC).

The sample consisted of 109 nurses of which 89 (81.7%) were female and 20 (18.3%) were male.

The age range was 19 to 69 years (Mean = 38.94 years; SD = 11.62).

These nurses scored a mean of 9 years in their work (Range = 1 to 39 years; SD = 8.97).

21 (19.3%) worked a morning shift, 16 (14.7%) an afternoon shift, and 27 (24.8%) a night shift (just 1 worked in two shifts, 0.9%). 28 (25.7%) worked other shifts, such as continuous shift (15, 13.8%) and weekend shift (13, 11.9%).

16 did not mention their shift (14.7%).

The main work areas were patient rooms (28.4%), guard station (15.6%), intensive care ward (16.5%), neonatology (10.1%), others (18.1%, i.e. ambulances, surgery, etc.), and undefined by the respondent (11%).

Anomalous Experiences in Nurse & Health Workers Survey

The Anomalous Experiences in Nurse & Health Workers Survey was used, which is a self-report that has 13 yes/no items designed (Cronbach’s alpha = .78) following a previous study (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017).

Items of anomalous (or spiritual) experiences during hospitalization include sense of presence and/or apparition, floating lights, or luminescences, hearing strange noises, voices or dialogues, crying or moaning, seeing energy fields, lights, or “electric shock” around or coming out of an inpatient, etc.

Other indications might include having an extrasensory experience, a malfunction of equipment or medical instrument with certain patients, or a spiritual form of intervention (e.g., prayer groups, laying on of hands, rites, images being blessed).

The survey also evaluates age, length of service, shift (morning, afternoon, or night), hospital area (patient rooms, guard station, intensive care, neonatology, others), and name of institution (confidential).

Email or phone information was optional.

The questions were also split into two types:

Type 1: Nurses as listeners to the anomalous experiences from patients (i.e. near-death or out-of-body experiences) and from other (trustworthy) nurses (items 1, 2, 6, 12, and 13), and

Type 2: Nurses as experiencers themselves of anomalous experiences (items 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11).

This separation is important to provide information to help us understand anomalous experiences.

Results

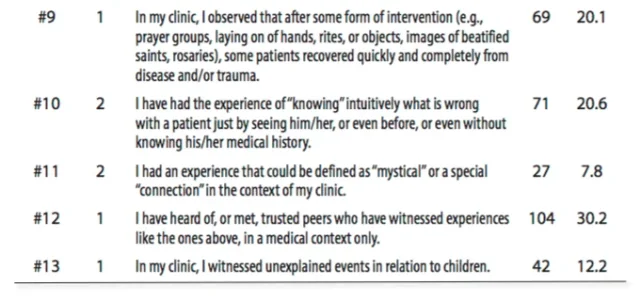

The most common anomalous experiences reported under Type 2 (as experiencers) are sense of presence or apparitions (28.8%), hearing strange noises, voices or dialogues, crying or complaining (27%), knowing the patient’s disease intuitively (20.6%).

Under Type 1, the rankings of experiences as listeners of experiences of their patients were: near-death experiences (25.6%), religious intervention (20.1%), and anomalous experiences in relation with children (12.2%) (see Table 1).

Discussion

The results showed that of the 235 nurses who reported having had at least one anomalous experience in a hospital setting, the most common anomalous experiences reported as experiencers, are sense of presence or apparitions, hearing strange noises, voices or dialogues, crying or complaining, and knowing the disease intuitively; and as listeners of experiences of their patients/peers, near-death experiences, religious intervention, and anomalous experiences in relation with children.

Hence, in the context of this study, the distinction between purely subjective experiences and those considered paranormal (veridical) is irrelevant.

Even veridical experiences may depend on the same psychological predispositional factors as do non-veridical experiences.

A high prevalence of anomalous experiences in nurses at work could lead them toward acceptance of the voices sometimes reported by clients.

Nurses may listen to these experiences and seek to understand them by perceiving them as similar to their own, rather than fundamentally different, incomprehensible, or even schizophrenic.

It could lead nurses to explore where, when, and how the experiences took place.

As nurses have anomalous experiences, too, professionals can begin to understand the experience as not inherently bad and in need of elimination—rather, it is a common experience that we can accept and try to make sense of.

Generally speaking, there are a number of drawbacks connected with this research in hospital settings as they are conservative institutions, unlikely to be open about their population and even more so with respect to providing information relating to the subject of this investigation.

The nurses did reveal their personal and professional experiences and those of their patients, noting that they considered experiences of paranormal phenomena within a hospital setting not to be infrequent or unexpected.

They were not frightened by their patients’ experiences, or their own, and exhibited a quiet confidence about the reality of the experiences for themselves and for the patient or dying person.

Acceptance of these experiences, without interpretation or explanation, characterized their responses.

By reassuring them that the occurrence of paranormal phenomena is not uncommon and is often comforting to the dying person, we may assist nurses to be instrumental in normalizing a potentially misunderstood and frightening experience.

There is evidence that the sensed presence is a common concomitant of sleep paralysis particularly associated with visual, auditory, and tactile hallucinations, as well as intense fear.

Recent surveys suggest that approximately 30% of young adults report some experience of sleep paralysis (Cheyne, Newby-Clark, & Rueffer 1999, Fukuda et al. 1998, Spanos et al. 1995).

Visions of ghosts may be related to cognitive processes involving fantasy and cognitive perceptual schizotypy proneness, which are correlated with each other (Parra 2006).

Although the recruiting procedure of the survey was voluntary instead mandatory, it might be skewed toward people with more interest in the subject, particularly as a result of their own experiences.

However, future studies will be conducted using a qualitative study to explore palliative care nurses’ experiences, to reflect on the influence of these experiences on the care of dying patients and their families and friends, and to contribute to the limited nursing literature on the topic.

The response of health professionals, specifically nurses, to anomalous experiences is an area not widely reported (Kellehear 2003).

Even palliative care literature is mostly silent on this topic.

Indeed, the study of anomalous experiences is an area of much contention in many fields.

Acknowledgments

This research project was supported by the BIAL Foundation (Grant 246/14).

Thanks are due to Mónica Agdamus, Sergio Alunni, Rocío Ba- rucca, Ricardo Corral, Silvia Madrigal, Jorgelina Rivero, Jorge Sabadini, Rocio Seijas, Osvaldo Stacchiotti, Andrés Tocalini, Stella Maris Tirrito, and Esteban Varela for contacting the Research and Teaching Area of the Nurs- ing Department of each hospital.

Thanks are also due to Rocio Seijas and Paola Giménez Amarilla for data entry and phenomenological analysis, and to Juan Carlos Argibay for his useful methodological and statistical advice.

References Cited

Barbato, M., Blunden, C., Reid, K., Irwin, H., & Rodriguez, P. (1999). Parapsychological phenomena near the time of death. Journal of Palliative Care, 15(2):30–37.

Barret, W. F. (1926). Death-bed Visions: The Psychical Experiences of the Dying. London: Bantam. Betty, S. L. (2006). Are they hallucinations or are they real? The spirituality of deathbed and near-

death visions. OMEGA, 53:37–49.

Brayne, S., Farnham, C., & Fenwick, P. (2006). Deathbed phenomena and its effect on a palliative

care team. American Journal of Hospital Palliative Care, 23:17–24.

Brayne, S., Lovelace, H., & Fenwick, P. (2006). An understanding of the occurrence of deathbed phenomena and its effect on palliative care clinicians. American Journal of Hospice and

Palliative Medicine, (Jan.–Feb.).

Cheyne, J. A., Newby-Clark, I. R., & Rueffer, S. D. (1999). Relations among hypnagogic and and

hypnopompic experiences associated with sleep paralysis. Journal of Sleep Research,

8(4):313.

Fenwick, P., & Fenwick, E. (2008). The Art of Dying. London, UK: Continuum.

Fukuda, K., Ogilvie, R. D., Chilcott, L., Vendittelli, A.-M., & Takeuchi, T. (1998). The prevalence of

sleep paralysis among Canadian and Japanese college students. Dreaming, 8(2): 59–66.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:DREM.0000005896.68083.ae

Katz, A., & Payne, S. (2003). End of Life in Care Homes. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Kellehear, A. (2003). Spirituality and palliative care: A model of needs. Palliative Medicine, 14:149– 155.

O’Connor, D. (2003). Palliative care nurses’ experiences of paranormal phenomena and their influence on nursing practice. Presented at 2nd Global Making Sense of Dying and Death Inter-Disciplinary Conference, November 21–23, 2003, Paris, France.

Osis, K., & Haraldsson, E. (1977). Deathbed observations by physicians and nurses: A cross- cultural survey. Journal of the American Society for Psychical Research, 71:237–259.

Osis, K., & Haraldsson, E. (1997). At the hour of death. London, UK: United Publishers Group. Parra, A. (2006). Psicología de las Experiencias Paranormales: Introducción a la teoría, investigación

y aplicaciones terapéuticas. Buenos Aires: Akadia.

Parra, A. (2015). Personality traits associated with premonition experience: Neuroticism,

extraversion, empathy, and schizotypy. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 79(1),

(918), 1–10.

Parra, A., & Argibay, J. C. (2012). Dissociation, absorption, fantasy proneness and sensation-

seeking in psychic claimants. Journal of the Society for Psychical Research, 76.4:193–203. Parra, A., & Giménez Amarilla, P. (2017) Anomalous/paranormal experiences reported by nurses

in relation to their patients in hospitals. Journal of Scientific Exploration, 31:11–29. Spanos, N. P., McNulty, S. A., DuBreuil, S. C., Pires, M., & Burgess, M. F. (1995). The frequency and correlates of sleep paralysis in a university sample. Journal of Research in Personality,

29(3):285–305.

Tellegen, A., & Atkinson, G. (1974). Openness to absorbing and self-altering experiences

(“Absorption”), a trait related to hypnotic susceptibility. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 83:268–277.

344 nurses were grouped as 235 experiencers and 109 non- experiencers.

The most common experiences are sense of presence and/or apparitions, hearing noises, voices or dialogues, crying or complaining, and intuitions and extrasensory experiences as listeners of the experiences of their patients, such as near-death experiences, religious interventions, and many anomalous experiences in relation with children (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017).

Introduction

It is important to note that the findings related to anomalous experiences by nurses (Barbato et al. 1999, O’Connor 2003) have also been reported by doctors (Osis & Haraldsson 1977, 1997) and other caregivers in hospital settings (Brayne, Farnham, & Fenwick 2006, Katz & Payne 2003, Kellehear 2003, Fenwick & Fenwick 2008), and in care homes (Katz & Payne 2003) around a number of anomalous events such as deathbed visions (Barret 1926, Betty 2006, Brayne, Farnham, & Fenwick 2006, Brayne, Lovelace, & Fenwick 2006).

A previous, up-to-date study on anomalous experiences in hospital settings (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017), recruited nurses (n = 100) who reported a number of anomalous experiences from one health center in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Four potential traits that could “modulate” anomalous experiences in nurses are work stress, hallucination proneness, heightened attentional capacities (psychological absorption) associated with a number of anomalous experiences, and “openness” to such experiences.

It could be argued that the psychological pressure of the working conditions of nurses triggers such anomalous perceptual experiences, but a comparison between nurse experiencers and a control group in terms of work stress (i.e. nurses who reported these experiences tended to experience greater work- related stress) was not confirmed (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017).

Parra and Giménez Amarilla (2017) also found that those who reported a combination of unusual perceptual experiences and a high level of psychological absorption—a state of heightened imaginative involvement in which an individual’s attentional capacities are focused in one behavioral domain (Tellegen & Atkinson 1974)—tended to score higher for anomalous experiences compared with those who did not report such experiences.

In fact, a better predictor than work stress and hallucination-proneness was psychological absorption in experiencers compared with the control group (Parra 2015, Parra & Argibay 2012).

Of the 100 nurses they surveyed, 61 of them reported having had at least one anomalous experience in a hospital setting, the most common feelings reported were a sense of “presence” (30%), hearing noises and finding no source (17%), and knowing intuitively what was wrong with a patient without knowing their medical history (14%), patients with near-death experiences (19%), patients recovering quickly and completely from disease after religious intervention (e.g., prayer group) (18%), and anomalous experiences where children were involved (15%).

The present study represents a replication utilizing a larger number of nurses from a wider range of hospitals and health centers in Buenos Aires.

The main aim was to determine frequency and percentage of anomalous experiences across multiple hospital/health centers instead of from just one.

Methods

Participants

A total of 450 questionnaires were sent to nurses in 36 different hospitals and health service departments.

Of these, 344 (76%) usable questionnaires were returned.

The nurse participants were recruited with the cooperation of their Research and Teaching areas of the Nursing Department of each (the Principal Nursing Officers).

They gave us permission to administer the set of questionnaires, which were distributed through the Nursing Officers to each nurse in the hospital, depending on the number of nurses working in each hospital and health center (Mean = 100; Rank = 5 to 300 per hospital approximately).

The Nursing Officers verbally explained the research to each nurse on all shifts.

The Nursing Officers were also contacted through announcements in hospitals and the Internet (briefly stating the main aims of the research), and many nurses interested in spiritual/paranormal topics contacted the Nursing Officers in their hospital, some of whom also showed interest in the topic.

Another group of Nursing Officers also was contacted by the researcher who briefly stated the main aims of the study, but no hypothesis was given to the nurses employed in the hospitals.

All nurses completed the questionnaires in isolation and they returned them at the same time (the time to complete the set of questions was forty minutes).

Some nurses (n = 80) were also recruited from courses and seminars through nursing schools and health centers seminars, where the questionnaires were completed in a classroom setting with the permission of their teachers and directors.

Consent Form

The set of questionnaires included a consent form.

The nurse participants were informed that we were recruiting information on anomalous and/or spiritual experiences and they signed an appropriate consent form.

They all received significant information about the procedure and were free to decline to participate.

All data collected were treated confidentially.

Categorization Procedure

The following criteria were used to split the sample into two groups: Nurses who indicated “one time” and/or “multiples times” for (at least) one of the 13 items were categorized as the Nurse Experiencers “NEs” group (n = 235), and Nurses who indicated “never” for all 13 items were categorized as the “Control” group (n = 109).

Eight items of the Anomalous Experiences in Nurse & Health Workers Survey were used to create an Index of total experiences, that is, nurses as anomalous experiencers themselves, but nurses as listeners of the experiences from patients and other nurses were excluded (five items).

Participants

Nurse experiencers (NE).

The sample consisted of 235 nurses, of which 183 (78%) were female and 52 (22%) were male.

The age range was 19 to 68 years (Mean = 39.19 years; SD = 11.15 years).

Nurses scored a mean of 11 years in their work in hospitals (Range = 1 to 48 years; SD = 10.52).

39 (16.6%) of them worked a morning shift, 51 (21.7 %) an afternoon shift, and 45 (19.1%) the night shift (just 6 work in two shifts, 2.6%).

66 (31.8%) worked in other shift modes such as continuous shift (37, 15.7%) and weekend shift (29, 12.3%), and 28 did not mention the shift (11.9%). The main work areas surveyed were patient rooms (24.3%), guard station (13.2%), intensive care ward (22.1%), neonatology (7.7%), others (22.2%, i.e. ambulances, surgery, etc.), and undefined by the respondent (8.9%).

Nurse controls, nonexperiencer nurses (NC).

The sample consisted of 109 nurses of which 89 (81.7%) were female and 20 (18.3%) were male.

The age range was 19 to 69 years (Mean = 38.94 years; SD = 11.62).

These nurses scored a mean of 9 years in their work (Range = 1 to 39 years; SD = 8.97).

21 (19.3%) worked a morning shift, 16 (14.7%) an afternoon shift, and 27 (24.8%) a night shift (just 1 worked in two shifts, 0.9%). 28 (25.7%) worked other shifts, such as continuous shift (15, 13.8%) and weekend shift (13, 11.9%).

16 did not mention their shift (14.7%).

The main work areas were patient rooms (28.4%), guard station (15.6%), intensive care ward (16.5%), neonatology (10.1%), others (18.1%, i.e. ambulances, surgery, etc.), and undefined by the respondent (11%).

Anomalous Experiences in Nurse & Health Workers Survey

The Anomalous Experiences in Nurse & Health Workers Survey was used, which is a self-report that has 13 yes/no items designed (Cronbach’s alpha = .78) following a previous study (Parra & Giménez Amarilla 2017).

Items of anomalous (or spiritual) experiences during hospitalization include sense of presence and/or apparition, floating lights, or luminescences, hearing strange noises, voices or dialogues, crying or moaning, seeing energy fields, lights, or “electric shock” around or coming out of an inpatient, etc.

Other indications might include having an extrasensory experience, a malfunction of equipment or medical instrument with certain patients, or a spiritual form of intervention (e.g., prayer groups, laying on of hands, rites, images being blessed).

The survey also evaluates age, length of service, shift (morning, afternoon, or night), hospital area (patient rooms, guard station, intensive care, neonatology, others), and name of institution (confidential).

Email or phone information was optional.

The questions were also split into two types:

Type 1: Nurses as listeners to the anomalous experiences from patients (i.e. near-death or out-of-body experiences) and from other (trustworthy) nurses (items 1, 2, 6, 12, and 13), and

Type 2: Nurses as experiencers themselves of anomalous experiences (items 3, 4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11).

This separation is important to provide information to help us understand anomalous experiences.

Results

The most common anomalous experiences reported under Type 2 (as experiencers) are sense of presence or apparitions (28.8%), hearing strange noises, voices or dialogues, crying or complaining (27%), knowing the patient’s disease intuitively (20.6%).

Under Type 1, the rankings of experiences as listeners of experiences of their patients were: near-death experiences (25.6%), religious intervention (20.1%), and anomalous experiences in relation with children (12.2%) (see Table 1).

Discussion

The results showed that of the 235 nurses who reported having had at least one anomalous experience in a hospital setting, the most common anomalous experiences reported as experiencers, are sense of presence or apparitions, hearing strange noises, voices or dialogues, crying or complaining, and knowing the disease intuitively; and as listeners of experiences of their patients/peers, near-death experiences, religious intervention, and anomalous experiences in relation with children.

Hence, in the context of this study, the distinction between purely subjective experiences and those considered paranormal (veridical) is irrelevant.

Even veridical experiences may depend on the same psychological predispositional factors as do non-veridical experiences.

A high prevalence of anomalous experiences in nurses at work could lead them toward acceptance of the voices sometimes reported by clients.

Nurses may listen to these experiences and seek to understand them by perceiving them as similar to their own, rather than fundamentally different, incomprehensible, or even schizophrenic.

It could lead nurses to explore where, when, and how the experiences took place.

As nurses have anomalous experiences, too, professionals can begin to understand the experience as not inherently bad and in need of elimination—rather, it is a common experience that we can accept and try to make sense of.