You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Merkabah

- Thread starter Skarekrow

- Start date

More options

Who Replied?Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Wow, I do like me some Gothic plateThanks, Skare!

It's pretty amazing stuff!Nice! I need them

@Wyote - How about a 3D print challenge?!

Ihttps://coinsweekly.com/maximilian-is-legendary-armor-in-new-york/

Hope you both are doing really well!?

@Daustus

Thanks for reading too man!

Much love everyone!

:<3white:

I love it!!!

Thanks!

It was a lot of work, but the kitchen and surrounding area needed it desperately!

The cabinets were that awful "honey oak" blah!

The bookcase space was this totally unusable space since it is too high to get to anything without a ladder.

We reengineered some IKEA bookcases and cut them in half - then connected them together lengthwise into a 15 foot span.

I climbed into the attic and anchored it in with some heavy duty bolts and it's very sturdy.

The ladder was a lucky find...we were looking for a wooden library ladder but this came up for sale on Craigslist for only $80!

It was in perfect working order and was only a few years old.

We looked it up online when I was ordering the brackets and the rail for the ladder and new the ladder runs about $850+!!

All in all, we made the bookcase, and got the ladder for less than $300.

Not too shabby.

Take care!

:<3white:

Thank you, Skare! Cool home, too!

Thank you!

I thought you might like that painting.

Also, I listened to this the other day and it made me think of you as she talks about her relationship with her art and how she feels about it being appropriated in a capitalist society amongst other things.

I found it an interesting talk and would bet she is an INFJ herself.

Have a peaceful day!

:<3white:

Jenny Odell, How to Do Nothing - XOXO Festival (2019)

In her first book, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, multi-disciplinary artist and writer Jenny Odell argues that taking control of our attention from the capitalist forces determined to monetize it and reconnecting with the world around us is a critical form of resistance.

In her first book, How to Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy, multi-disciplinary artist and writer Jenny Odell argues that taking control of our attention from the capitalist forces determined to monetize it and reconnecting with the world around us is a critical form of resistance.

Last edited:

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

The chemistry and psychology of kindness

By Sophie Kesteven

By Sophie Kesteven

During childhood, many of us are taught about the importance of kindness.

But are you aware of the different motivations behind kindness and the benefits it can have on yourself?

It's not uncommon to experience a "feel-good rush" after you've been kind to another person, says Dr James Kirby, a lecturer in clinical psychology at The University of Queensland.

"Sometimes people refer to it as the warm glow, and that's some of the endorphins that are being kicked back into the system, the internal reward system," he says.

So, is getting a regular rush of these endorphins as simple as just being more kind, more often?

Altruistic vs strategic kindness

A study conducted by psychologists at the University of Sussex in 2018 examined brain scans of more than a thousand participants who were carrying out acts of kindness.

It discovered that people benefit from acts of kindness regardless of whether they are strategically motivated (meaning there is something to be gained from their act of kindness), or altruistic (there is nothing in it for them) — but the "warm glow" effect was at its peak with altruistic acts of kindness.

"We found that there's a part of the brain that is even more active when we give away [acts of kindness] with no possible benefits for ourselves, so in the altruistic case," says Jo Cutler, a PhD student who co-authored the study.

"So, this is when that warm glow from kindness will be its strongest, and we saw the brain activity reflecting that."

The 'lost letter experiment'

Eager to get a better understanding of kindness, Cyril Grueter, senior lecturer at University of Western Australia, carried out a 'lost letter experiment' in Perth.

It involved dropping letters across different neighbourhoods, including low and high socio-economic suburbs, on two separate occasions.

In the first study, published in 2016, his team dropped 300 letters.

In the second study conducted more than a year later, 1,200 letters were dispersed in various areas.

To his surprise, on both occasions, 50 per cent of the letters that were dropped were returned.

"If you encounter a letter on the pavement and you pick it up and you post it, then that obviously means you have to go out of your way, you incur a cost — and that's exactly how we define altruism, incurring a cost to help someone else," he says.

"So that really tells us that humans have this innate kindness, otherwise they wouldn't do that."

"And to our surprise, again, we found that letters dropped in high socio-economic areas were more likely to be returned."

"We believe that it may have something to do with the fact that people in low socio-economic areas, they are more preoccupied with meeting their immediate needs. And whereas people in high-end suburbs, they may have slightly different priorities. But we can only speculate on why people in low-end suburbs were less likely to return a letter."

Benefits of self-kindness

Altruism is when an individual helps another person at their own expense.

Being kind to other people can have multiple benefits, but it's also just as important to be kind to yourself, stresses Dr Kirby.

"If I am being kind towards myself, the same regions light up if I'm receiving kindness from another person or giving kindness to another person," Dr Kirby says.

"That's why we tell people, when you have a setback or difficulty, what's the tone of your self-talk like? Do you talk to yourself in an aggressive, matter-of-fact, blunt way, or can you speak to yourself in a friendlier way?

"If you speak to yourself in a friendly way, much like a friend would in terms of trying to be kind and helpful, the same areas of the brain light up."

As a clinical psychologist, Dr Kirby adds that he works with a lot of people who feel they are unlovable and undeserving of kindness or compassion.

"They are very good at being kind to others but the very idea or thought of being kind to themselves is just completely foreign or a big no-no. They find it very threatening," he says.

"We all have this inner voice that is judgmental or commenting or narrating … monitoring how we are going and performing.

"You try to explore what's that about or where has this come from. Sometimes it can be, 'Oh, that's the way Dad spoke to me', or 'That's the way teachers spoke to me' so it has a long history.

"So, when you're seeing people in their 20s, 30s and 40s, that kind of voice has been there for years … a lot of people don't recognize that that inner tone can impact your physiology in your body much like if it was coming from someone else."

If you're wanting to start your day in the right mindset by being kinder to yourself, Dr Kirby has some words of advice:

"When you wake up in the morning, just welcome yourself."

Sounds odd, right?

"Yes, that sounds a bit funny," he laughs.

"But welcome yourself as if you're saying hello to a dear friend in your mind. I would say, 'Oh, good morning James'. Wake yourself with that joyful friendliness and playfulness, and that kicks off a different physiology in your body.

"As opposed to 'What, it's 6am, this is shit I have so much stuff to do'. That kicks off a stress physiology in your body, and already your stress levels are at their peak in the morning, and then they drop away across the day."

Then for 30 seconds or a minute, contemplate: "If I was to be at my kindest today, what would I do?"

"Just imagine what it would be like to walk around at your kindest. Then start your day."

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

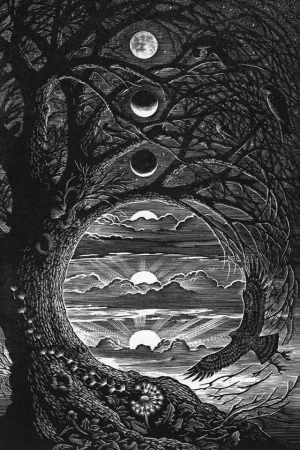

I've been having some very intense personal revelations lately.

The chronic pain I deal with is definitely getting worse in many ways...but mentally and emotionally the pain is affecting me less and less it seems.

It's taken some time but I feel my mental state in general is in a better place.

I'm eating better, finally feel back to normal two years after the pancreatic/gallbladder surgery...and though the lethargy from the arthritis is still difficult - mostly due to a screwy sleep schedule - I also am not letting it become a critique on myself by my ego-self.

Last night I was humming a random made up tune and all of the sudden I felt a connection that came with the realization that no matter what tune I am humming or singing to myself - there are others in the world who are at the same moment humming or singing to themselves parts of the song - even if you diverge after a single note, someone else would then come in to fill the correct one - it was like an orchestra of the collective consciousness was playing a grand concerto written by us all...jumping from person to person...I could really almost hear it all in my head.

There was that feeling...but also one of - all this was being uploaded to the universe, both from each perspective and collectively in every conceivable pattern...maybe we don't realize it when we are humming a simple tune to ourselves not even thinking about it, but put together properly, by some kind of grand consciousness or higher mind(s), source - and it's potentially something much more intricate, meaningful, and important...it becomes worth saving.

Difficult to describe...but I would implore you to try it as a meditation sometime...even the most simple tune or even single note hummed or even imagined in the mind - can be of contribution to an amazing melange of collective mind - perhaps we can learn to bring back the "music" we've gathered...if we could tap in and pull information out...seems plausible to me, I feel that certain people have been able to tap into the "source" or whatever you wish to call it to varying degrees over our human existence....pulling out poetry, music, art, scientific "discoveries", etc..

Anyhow...much love to you all!

Thank you everyone who takes the time to read this thread and my thoughts.

I appreciate you all and I appreciate all your contributions and support!

Much love all!

:<3white:

The chronic pain I deal with is definitely getting worse in many ways...but mentally and emotionally the pain is affecting me less and less it seems.

It's taken some time but I feel my mental state in general is in a better place.

I'm eating better, finally feel back to normal two years after the pancreatic/gallbladder surgery...and though the lethargy from the arthritis is still difficult - mostly due to a screwy sleep schedule - I also am not letting it become a critique on myself by my ego-self.

Last night I was humming a random made up tune and all of the sudden I felt a connection that came with the realization that no matter what tune I am humming or singing to myself - there are others in the world who are at the same moment humming or singing to themselves parts of the song - even if you diverge after a single note, someone else would then come in to fill the correct one - it was like an orchestra of the collective consciousness was playing a grand concerto written by us all...jumping from person to person...I could really almost hear it all in my head.

There was that feeling...but also one of - all this was being uploaded to the universe, both from each perspective and collectively in every conceivable pattern...maybe we don't realize it when we are humming a simple tune to ourselves not even thinking about it, but put together properly, by some kind of grand consciousness or higher mind(s), source - and it's potentially something much more intricate, meaningful, and important...it becomes worth saving.

Difficult to describe...but I would implore you to try it as a meditation sometime...even the most simple tune or even single note hummed or even imagined in the mind - can be of contribution to an amazing melange of collective mind - perhaps we can learn to bring back the "music" we've gathered...if we could tap in and pull information out...seems plausible to me, I feel that certain people have been able to tap into the "source" or whatever you wish to call it to varying degrees over our human existence....pulling out poetry, music, art, scientific "discoveries", etc..

Anyhow...much love to you all!

Thank you everyone who takes the time to read this thread and my thoughts.

I appreciate you all and I appreciate all your contributions and support!

Much love all!

:<3white:

Last edited:

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Pretty interesting...I'm not very musical either Carl...

[Carl Jung on Music and the Collective Unconscious]

To Serge Moreux

Dear M. Moreux, 20 January 1950

While I thank you for your kind letter, I must tell you that unfortunately I am obliged to limit my activity for reasons of age and health, and so it will not be possible for me to write an article for the projected number of Polyphonie.

Music certainly has to do with the collective unconscious-as the drama does too; this is evident in Wagner, for example.

Music expresses, in some way, the movement of the feelings (or emotional values) that cling to the unconscious processes.

The nature of what happens in the collective unconscious is archetypal, and archetypes always have a numinous quality that expresses itself in emotional stress.

Music expresses in sounds what fantasies and visions express in visual images.

I am not a musician and would not be able to develop these ideas for you in detail.

I can only draw your attention to the fact that music represents the movement, development, and transformation of motifs of the collective unconscious.

In Wagner this is very clear and also in Beethoven, but one finds it equally in Bach’s “Kunst der Fuge.”

The circular character of the unconscious processes is expressed in the musical form; as for example in the sonata’s four movements, or the perfect circular arrangement of the “Kunst der Fuge,” etc.

I am with best regards,

Yours sincerely,

C.G. Jung ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 542.

[Carl Jung on Music and the Collective Unconscious]

To Serge Moreux

Dear M. Moreux, 20 January 1950

While I thank you for your kind letter, I must tell you that unfortunately I am obliged to limit my activity for reasons of age and health, and so it will not be possible for me to write an article for the projected number of Polyphonie.

Music certainly has to do with the collective unconscious-as the drama does too; this is evident in Wagner, for example.

Music expresses, in some way, the movement of the feelings (or emotional values) that cling to the unconscious processes.

The nature of what happens in the collective unconscious is archetypal, and archetypes always have a numinous quality that expresses itself in emotional stress.

Music expresses in sounds what fantasies and visions express in visual images.

I am not a musician and would not be able to develop these ideas for you in detail.

I can only draw your attention to the fact that music represents the movement, development, and transformation of motifs of the collective unconscious.

In Wagner this is very clear and also in Beethoven, but one finds it equally in Bach’s “Kunst der Fuge.”

The circular character of the unconscious processes is expressed in the musical form; as for example in the sonata’s four movements, or the perfect circular arrangement of the “Kunst der Fuge,” etc.

I am with best regards,

Yours sincerely,

C.G. Jung ~Carl Jung, Letters Vol. 1, Page 542.

Last edited:

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

_____________________________________________________________

_____________________________________________________________

since feeling is first

By: E. E. Cummings

since feeling is first

who pays any attention

to the syntax of things

will never wholly kiss you;

wholly to be a fool

while Spring is in the world

my blood approves,

and kisses are a better fate

than wisdom

lady i swear by all flowers. Don’t cry

– the best gesture of my brain is less than

your eyelids’ flutter which says

we are for each other; then

laugh, leaning back in my arms

for life’s not a paragraph

And death i think is no parenthesis

E. E. Cummings

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

A blurry photo sent to me from a talk/Q&A on psychedelics/entheogens I participated in in 2017.

I'm the second from the right (not that you can really tell) - I know, it's a very high quality photo lol!

Anyhow...this was an intense talk - there was well over 500 people there that night I remember.

I'm the second from the right (not that you can really tell) - I know, it's a very high quality photo lol!

Anyhow...this was an intense talk - there was well over 500 people there that night I remember.

Last edited:

Daustus

What came first, the music or the misery?

- MBTI

- INFJ

- Enneagram

- 6w7