Ren

Seeker at heart

- MBTI

- INFJ

- Enneagram

- 146

It's interesting because I didn't feel that way at all when I read his book. I didn't feel like his critiques influenced my judgement. For example, he says pretty damning things about Nietzsche, but I came out of the book loving Nietzsche just as much. In fact I think I appreciated his work more as a result, because I saw it treated as a purely human creation, full of potential flaws, rather than as the superhuman product of a daunting "giant". All philosophers are fallible. That's what I like about them, and Russell does a great job of reminding us of it.

I wonder if being Ni-dom facilitates this kind of perspective, i.e. not being too bothered by what looks like harsh judgements and seeing through the substance underneath.

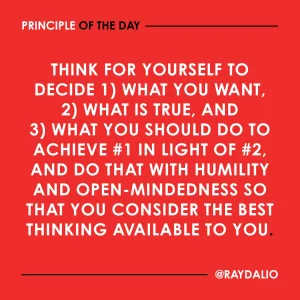

Just as an aside, I don't really agree with this. I mean, of course understanding requires openness, but I've often found that the best philosophers are those who are capable of engaging critically with the works of the "giants". And engaging critically must involve a dimension of judging---at the end of the day you have to say if you think the "giant" is correct or not. Heck, I just love how Russell criticises Aquinas, where everyone seems to spend the time just wildly masturbating over his supreme genius He doesn't care about the reputation of a thinker, he doesn't factor that into his critiques. I think this is the mark of an independent mind.

He doesn't care about the reputation of a thinker, he doesn't factor that into his critiques. I think this is the mark of an independent mind.

I wonder if being Ni-dom facilitates this kind of perspective, i.e. not being too bothered by what looks like harsh judgements and seeing through the substance underneath.

New If I learned anything over the years, it's that judging a thing is easier than understanding it from the correct point of view (not from your perspective).

Just as an aside, I don't really agree with this. I mean, of course understanding requires openness, but I've often found that the best philosophers are those who are capable of engaging critically with the works of the "giants". And engaging critically must involve a dimension of judging---at the end of the day you have to say if you think the "giant" is correct or not. Heck, I just love how Russell criticises Aquinas, where everyone seems to spend the time just wildly masturbating over his supreme genius