If I were to describe my political views to you, I'm not sure they'd make much sense in terms of how people have been conditioned to digest 'politics' in the last century or two.

In general I might say something like 'I'm

of the "left", but I

believe in the "centre"', but that's not entirely accurate, either, since I have some opinions which could be rightly regarded as 'conservative', and I'm not ashamed of that despite being on balance 'progressive'.

The core value, though, revolves around the 'centre', or rather, 'the forum' (in the classical sense). I'm committed to the cooperative space of compromise and accord that exists within the core of our societies, and the lofty pillars of civility, respect, and truth which hold up the whole august structure.

There's that phrase of Aristotle's which is usually chucked about by people who want to make some kind of Machiavellian point about the scheming nature of human beings: 'man is a political animal'. However, I wouldn't translate it like this. I'd go with something more like, 'man is a

civic animal'; I think that's much closer to the sense of the original Greek. And, in fact, I think this is both what we need more of, and what I'm ultimately drawn to:

civics.

There's a couple of people on this forum who I think probably share this same commitment to the civic core as I do.

@Pin springs to mind, but when

@Reason speaks of 'the Republic', I get a powerful sense of it, especially. Reason and

@Asa recently had an exchange in the former's blog which indicated to me that Asa has the same commitment.

In fact, I

love to see open displays of that commitment - that respect - and they stick in my heart as memories or knowledge very important to me. I'm thinking of things like the friendship between Tony Benn and Enoch Powell in the UK, or the respect between Barrack Obama and John McCain (encapsulated by his funeral) in the US, and now, of course, between Asa and Reason in our own community.

Conservatism

Conservatism really 'clicked' for me when I first came across the work of the conservative philosopher Sir Roger Scruton (in fact I just today watched a documentary of his on

beauty).

It was his concept of 'oikophilia' to describe the essential conservative mindset of the 'love of

home'. To be an oikophile in any sense is also to be conservative (whoever you vote for) - it's to say 'we

like it here. We want to

preserve the good things that we have.'

It is an attitude fundamentally vested in love.

The constant seeking to improve and change of the progressive is a noble cause; and so is the earnest desire of the oikophile - the conservative - to preserve and protect what is good. And, what's more, all of us have both of these feelings simultaneously.

For me, I am somewhat proud of the parliamentary tradition of my own country, and the legacy of democracy, liberality and 'science' of Europe more generally. I don't have to be an imperialist to

love those things from my own culture.

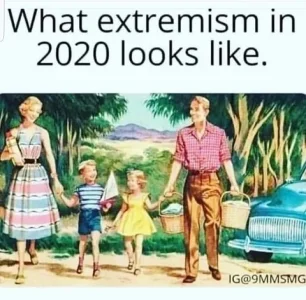

I also tend to place high value in the good that a traditional, stable family structure can provide for the raising of children. As someone raised outside of that, I feel this keenly. There is no hatred in valuing something like this.

Ultimately, I don't really have much tribal attachment to different approaches, systems and ideas. 'Socialism', 'capitalism' - these are mere 'technologies of statecraft' to me. Part of an arsenal of systems and structures from which we ought to pick and choose in the construction of ideal societies and states based on their utility to particular tasks. Marketise this, nationalise that; see what works best and readjust.