Very curious....

The hell if I will ever create a Tulpa on purpose though.

(Pretty sure I have on accident once or twice)

Tulpas originally did NOT just live in a persons’ head (as part of the article implies), but rather could act independently and would sometimes even turn on the creator...people have been possessed, physically harmed, etc.

This article does not consider any spiritual aspects of this phenomena which makes it incomplete imho as this is the history and nature of a Tulpa...not an online forum for imaginary friend enthusiasts, lol.

This is a totally materialist scientific viewpoint of the phantasm being created by the mind.

But I find it is good to not just feed my own confirmation bias and keep a well rounded understanding.

No matter what this dude writes about Tulpas though...I will never fuck around “creating” one.

Enjoy!

Making the strange familiar

The new subculture of Tulpamancy has garnered a lot of online

attention of late.

Tulpas, a concept borrowed from Tibetan Buddhism, are sentient imaginary friends conjured through ‘thoughtform’ visualization.

Tulpamancers are people who conjure Tulpas, and experience their imaginary companions as semi-permanent, non-threatening auditory ‘hallucinations’.

Other sense modalities like touch, emotions, and vision are also recruited in the experience.

Tulpamancers have been called the

weirdest culture on the internet.

As a cultural phenomenon, the practice has been described as a strange

secularization of the paranormal.

In the blogosphere, people have wondered if Tulpamancers have underlying mental illnesses, and if it is possible to hear voices without being crazy. Others have wondered if they are telling the truth.

How is it possible—is it possible at all?—to create a mental being that lives inside your head?

In this article, the first of two posts on the subject, I address popular myths and questions about Tulpamancy, and show that there is nothing inherently strange about the practice.

I expand on its positive and therapeutic aspects, and argue that studying Tulpamancy can help us move beyond simplistic understandings of mental illness.

I also present this new phenomenon as a fascinating example to understand the influence of culture on inner experiences.

In doing so, I invite readers to consider the limitations that contemporary culture places on imagination, our senses, and what we accept as real, normal, and desirable.

As a cognitive anthropologist who has

studied Tulpamancy closely, I have sought to apply the old intellectual recipe of

making the strange familiar and making the familiar strange.

This is an approach that was championed by

Margaret Mead, a key early figure in my discipline.

In her study of growing up in Samoa in the 1920s, Mead examined the ‘strange’ culture of adolescents in the Western Pacific who did not appear to undergo the ‘normal’ stress and turmoil of what was then (as it still is now) understood to be a difficult hormonally-mediated transition from

childhood into adulthood.

The lack of sexual restrictions in ‘adolescent’ lives in Samoa at the time had also seemed strange to Mead.

Returning to the U.S., she now saw what she had taken for granted with fresh eyes.

Could it be, she asked, that the distress experienced by American

teenagers and the taboos on youth

sexuality in western culture at large were in fact quite strange?

Could it be that what she had assumed to be a universally harrowing human experience was in fact grounded in the specific ways of a particular culture at a particular time?

Why Tulpamancers are not crazy.

In seeking to make the strange familiar, I have found that Tulpamancers, far from being crazy, were simply cultivating fundamentally normal dimensions of human

cognition and sociality.

I describe these mechanisms in part 2 of this series.

Tulpamancers reported overwhelmingly positive experiences, overall increased

happiness, and more

confidence in challenging social situations through the assistance of their Tulpa companions.

Many of those who had identified with specific psychopathological labels like

depression,

anxiety, or

ADHD similarly spoke of overall improvement.

When queried independently, Tulpas often described being ‘immune’ to the specific conditions of their hosts.

Autism Spectrum Disorders presented something of an exception.

One Tulpa explained that “having the same brain” as his host, both were necessarily bound to similar limitations.

Others reported greater degrees of freedom from their hosts’ conditions..

One of the first conclusions of my research was that conjuring Tulpas could make one more empathetic.

This is not a surprising finding.

Focusing one’s attention and affect on other people (real or imaginary), as we do

when we read fiction or watch movies, has been amply demonstrated to increase

empathy—that is, to makes us better at intuitively relating to other people, or being able to imagine what it is like to be somebody else in different situations.

Other findings pointed to further therapeutic possibilities.

A small minority of Tulpamancers, for example, already experienced voices before thinking of them as Tulpas, or turning them into friendly companions.

Some simply thought of them as imaginary friends.

Others had had difficult, or scary experiences with their voices and the characters that lived in their mind, and had come to understand them as a sign of illness.

In these instances, simply getting to know the voices, learning to talk to them as friends, and sharing the experience with other Tulpamaners seemed to lead to very positive results.

This approach, once again, is not new.

The dutch psychiatrist Marius Romme, for example, has developed a successful approach called “

living with voices” to help people with

psychosis turn their voices into friendly ones.

I want to insist that ‘hallucinations’ and ‘psychosis’ are not a productive terms to think of Tulpa experiences, and voice-hearing experiences at large.

It is both too simplistic and inaccurate to think of voice-hearing as a necessarily pathological experience.

In modern-day

psychiatry, the presence of non self-authored thoughts is often, but not always understood as a sign of mental illness.

In practice, one can only speak of pathology when there are clear signs of distress.

If a person describes her inner experiences as being scary,

stressful, or as preventing her from functioning well in everyday life, or if others around her report being scared or prevented from functioning by her behaviour, then we can safely speak of pathology.

As we have seen, this is far from being the case with the vast majority of Tulpamancers.

Whether ‘thinking’ is always or ever ‘

self-authored’ is too complex a philosophical question to tackle here.

It raises, for one, intractable questions about the nature of Consciousness and the Self, and equally hard questions about the problem of

Free Will.

It poses very difficult questions about the nature and role of the body, emotions, moods, and drives.

It also raises hard questions about the nature and role of language and culture, their relationship with behaviour,

intuition, and inner-narration, and their variations across social groups.

Tulpamancers, as we will see, show us something fascinating about cultural variations in the

positivity and negativity of the voice-hearing experience, and the fuzziness of narrative consciousness in general.

But first, we should appreciate what little we know about what goes on inside people’s heads.

Studying inner experience

Many people want to know if Tulpamancers are telling the truth about the experiences.

Their claims do seem hard to validate.

At face value, however, they are no more or less difficult to study than the claims made by anyone about what goes on in their heads.

While we have every reason to believe that people around us are conscious, have inner experiences, feel pleasure and pain, and have streams of narrative in their head, we have absolutely no way to study these experiences scientifically or to prove that any of this is going on.

In

philosophy, this is known as the

Problem of Other Minds.

For a while, progress in neuroimaging seemed to carry the promise that the so-called

Hard Problem of Consciousness would be solved, and that

neural underpinnings, or even causes of these processes would be discovered.

But no such breakthrough occurred.

While we can sometimes make good hypotheses about the brain regions associated with different kinds of tasks and behaviours (including

thinking about other people) these posited neural “signatures” or “correlates” tell us nothing whatsoever about the content and quality of people’s experiences.

We know, to present an analogy, that people’s heart-rates accelerate when they experience positive (eustress) and negative (stress) arousal.

This is a physiological signature of arousal.

But heart-rate measurements tell us nothing about what the person is feeling.

So it goes with brain imaging.

Verbal

reports elicited from individuals or personal introspection, as anecdotal as they seem, are still the best “evidence” we have for any kind of mental and bodily phenomena.

Most people, to make the matter worse, are quite unskilled at noticing, attending to, monitoring, and reporting on minutiae of their experiences, which makes the problem even harder to study.

Working with Tulpamancers, however, like

working with meditators, is a treat for phenomenologists (scholars who study inner experience), because they have trained themselves to be more attentive to their experiences than the average population.

When a large group of people report similarly fine-grained experiences that are comparable (in that they differ from average experiences reported by other groups) this is pretty good “evidence” for their veracity.

Relying on first-person reports does not preclude the possibility of quantitative measures.

When I surveyed

a group of 160+ Tulpamancers on the quality of their voice-hearing experience, for example, I found that most subjects who reported hearing their Tulpas’ voices “as distinctly as another person’s voice” had been practicing Tulpamancy for two years or more.

Practitioners with less experience, in turn, tended to report voices that were more thought-like, or halfway between their own thoughts and somebody else’s voice.

That tulpamancers in similar stages of the practice describe comparably similar experiences tending toward full-fledged automatized voices adds further validity to these reports.

These findings are consistent with what we are beginning to understand about auditory ‘hallucinations’.

A

recent study published in the Lancet, for example, found that against simplistic folk notions of auditory hallucinations heard as actual voices, schizophrenic patients also reported fine-grained distinctions between thought-like and other-voice-like experiences.

Voice-hearing across cultures

Recent work in psychological anthropology has also yielded more myth-busting findings on the content and affective dimensions of voice-hearing across cultures, and the relationship between people, their voices, and the implicit expectations shared by other members of their societies.

In a recent project, Stanford University’s

Tanya Luhrmann led a global team of anthropologists and psychiatrists who asked people diagnosed with

schizophrenia in

India, Ghana, and the United States what their voices were telling them.

Their fascinating results, in classical Margaret Mead fashion, showed that the mean, terrifying, threatening, debilitating character most of us associate with psychosis were much more pronounced with Western patients, and were likely to be rooted in biases inherent to Euro-American culture.

In Ghana and India, patients were more likely to report friendly and guiding voices, and hearing the voices of relatives.

When voices were teasing or mocking, they did so in much less violent ways.

In the Chennai sample, even voices that were actively disliked by patients tended to give commands consistent with family obligations such as “go to the kitchen and prepare food”, or “you need to eat, but not too much”.

In the California sample, patients were much more likely to describe their voices as violent, and spoke of their experience as meaning that they were “crazy”.

Source: Tanya M. Luhrmann, Padmavati, Hema Tharoor, Akwasi Osei / Topics in Cognitive Science 7 (2015) 646–663, p650

Cultural Invitations - Cognitive Ideology

This led Luhrmann and colleagues to develop a theory of “social kindling”, or “cultural invitations” in the mediation of psychosis.

What we pay attention to and how we make sense of it, the authors of the study argued, is always subtly influenced by our culture—that is, by how we expect others around us to think the world works.

They explained that implicit “cultural invitations” on how one should behave, how to make sense of and value experience, but also on what counts as a mind, a person, a spirit, a normal experience, and a pathological one can have an immense effect on how we feel.

This is something I have called “

cognitive ideology”, or the power of culturally-specific ideas and biases on what counts as a mind, what counts as real, and what counts as “normal”, desirable, or undesirable experience in shaping our most intuitive modes of affect and action.

Responding to latent cultural beliefs

As we will see, positive and negative inner experiences, and

“anomalous” experiences of all kinds also occur on a spectrum of implicit to explicit responses to deeply held, but often

unconscious cultural assumptions.

The work of the late psychologist

Nicholas Spanos, who spent a lifetime studying such “strange” experiences as

hypnosis, multiple personalities,

false memories, UFO abduction reports, and past-life recall, played an important role in our understanding of the relationship between culture and inner experience.

Through his clinical experiments and reviews of these strange cases, Spanos developed a sociocognitive hypothesis to explain how subjective reality responds to largely implicit, but elaborately “rule-governed” collectively held ideas.

He famously pointed out, for example, that reports of UFO abductions from individuals who appear convinced that they underwent the experience typically involve alien technology that is collectively imaginable, but not yet attainable.

The first reports of sighting and abductions in the pre-modern period, thus involved flying ships with sails.

It was possible to imagine the not-yet-attainable technology of flying ships, but not yet collectively imaginable to think of ships with no sails.

In the post-Apollo, post-Star Wars era, on this account, it has become collectively imaginable to think of such currently unattainable technologies as light-speed travel and teleportation.

This points to the importance of appreciating the role of culture in shaping one’s latent ideas, or implicitly held beliefs.

Simply put, these are deeply held expectations about what is true, false, right and wrong that we do not know we hold, but that shape our automatic behaviors.

Most of us are not very reflective about our own biases.

They tend to manifest themselves in our most “personal” tastes, preferences, intuitions, and avoidance or

attraction mechanisms.

But these responses are, as Spanos would have put it, rule-governed cultural constructs nonetheless.

Racist and sexist biases are infamous examples of such implicit beliefs picked up from latent cultural ideologies.

They can easily be studied in children through attribution tasks, such as the famous

Clark Doll Experiment.

In this experiment, children are asked to express their preference for one of two dolls, depicting a black and white babies.

Worryingly, even black children tend to express preference for the white doll.

How does this happen?

In the past 70 years of research on racial

bias, studies have consistently shown that across cultures, children as young as age 4 have already acquired biases about

ethnicity and other socially constructed categories of persons that are consistent with the dominant culture of their societies.

In most cases, however, these biases are not consciously held by the children’s caregivers and educators, and they are almost never explicitly taught.

It is as though the biases are literally “picked up” from a fuzzy cultural soup.

How such

biases are acquired -- indeed, how

broader cultural grammars are acquired -- is still an open question.

Source: Flying Ships / (c) Luigi Prina, Milan

I presented the mystery of how a latent architecture of cultural expectations and behaviours is acquired, and emphasized that this process extends to hallucinations, imagination, embodiment, and inner experiences at large.

But we should be cautious in assuming an “anything-goes” formula, where anyone can mentally improvise from a public language to hallucinate, conjure sentient voices, feel like they are abducted by aliens, or have out of body experiences.

Spanos’ work, we should note,

has been criticized for overemphasizing the social, and failing to give appropriate consideration to the individual psychological traits of people who are more prone to anomalous experiences than others.

Hypnotizability, proneness to absorption (the ability to become fully immersed in one’s inner imagery) and proneness to dissociation are examples of traits that are known to

occur on a spectrum across populations, and are likely be be innate.

Fantasy-proneness, a hypothesized sub-type of absorption, has also been identified (albeit more controversially) in people who report anomalous experiences.

Another standard explanation for anomalous experiences is that they occur as a response to repressed

memories and

trauma.

In a response to his critics, Spanos tested for trauma and traits variables in

a study that divided subjects who reported UFO experiences into

non intense (e.g., seeing lights and shapes in the sky) and

intense (e.g., seeing and communicating with aliens or missing time) groups.

He found that subjects in both groups did not score higher than average on psychopathology, hypnotizability, and fantasy proneness, but that experiences in the intense group were more often

sleep-related (e.g., sleep paralysis).

Subjects in the intense group also reported much stronger beliefs in the existence of aliens and space visitation.

Learning to Hear Voices: Explicit beliefs and the training of absorption.

Spanos’ findings on the intense UFO experiences group adds further evidence to the claim that culture shapes inner experience.

In this case, we should note the importance of explicit beliefs in the mediation of experience.

People who are consciously involved in believing, expecting, and desiring certain experiences, thus, may also be more prone to achieving these experiences.

This can only occur when expectations are validated by the broader, and more implicit comfort of expecting that other people have similar expectations.

Anthropologists have long

documented incidences of trance, dissociation, spirit possessions, and other anomalous experiences that occur in ritual, often

spiritual contexts in the absence of trauma and pathology.

In such cases, such as

Candomblé spirit possession in Brazil or

Madagascar, these experiences are understood as normal and desirable.

Tanya Luhrmann, whose work on voices across cultures we reviewed earlier, also conducted fascinating long-term anthropological and psychological investigations of inner dimensions of prayer among Pentecostal Christians.

Luhrmann’s work demonstrated that, in a process not unlike Tulpamancy, the hard work of prayer could eventually lead to voice-hearing experiences among believers.

She initially hypothesized that learning to hear the voice of God may require

a proclivity for absorption.

Her studies showed that those among her informants who reported the most vivid

mental imagery, greater focus, and more intense spiritual experiences scored higher on the Tellegen Absorption Scale (TAS).

Beyond the importance of proclivities, however, a key finding of Luhrmann’s research was that absorption could be trained and improved in practice. Luhrmann’s work elegantly showed that spiritual and other

unusual sensory experiences can become extraordinarily vivid as a result of attentional learning, particularly when they are sought after and rewarded in a community of people with similar beliefs.

In my own work, I also found that Tulpamancers scored higher than average on the Tellegen Absorption Scale.

Whether this reflects individual proclivities and personal types that are more likely to be interested in Tulpamancy than others is a difficult question.

My research, like Luhrmann’s, suggests that absorption-proneness can improve with practice, and that culture is an important factor in shaping the desirability and rewarding quality of unusual sensory experiences.

To make authoritative claims on Tulpamancy as an absorption-training practice, however, would require training non-Tulpamancers in the art of conjuring voices with longitudinal follow up of high and low absorption trait control groups.

Tulpamancy in popular culture: secular mysticism as resistance

Tulpamancers, as we have seen, are able to achieve highly individualized and unusual experiences that are, however, very similar in terms of their phenomenology.

It is precisely because Tulpamancy has become organized as a formalized culture (that is, a group of people united by shared expectations about the possibility and desirability of certain kinds of beings and states of affairs) that Tulpa experiences are at once possible, successful, and feel so positive to Tulpamancers.

The “fringe” dimension of Tulpamancy, on the one hand, helps foster solidarity among members and increases the

experiential rewards of having achieved such hard-to-reach, highly arousing experiences.

The biases of dominant Euro-American culture on unusual experiences, and mental experiences in particular, however, also create a difficult dynamic for Tulpamancers, who are often reluctant to “come out”, even to their closest friends, relatives, and acquaintances.

As news of the culture spreads online, Tulpamancers are likely to keep enduring mockery, ostracizing, and pathologization.

In this sense, the experience of such a fringe group is not unlike that of sufis, early christians, kabbalists, sadhus, and mystics of all kinds who were at once feared, revered, and oppressed in mass societies that demand rigid

conformity.

Such “mystics” threaten the very core of what most people accept as real and possible at the deepest and widest levels—their lives make us uncomfortable, because they point to the tragic limits of our imagination and the shallowness of our everyday experiences.

In the globalizing, internet-mediated world of 2016, Tulpamancers have to incur the perverse consequences of a culture in which difference is valorized in principle, but is mostly policed and punished in practice.

Our culture, paradoxically, nominally values individuality, but aggressively imposes a highly standardized framework on behaviour, which can be measured, catalogued, pathologized and punished with terrible precision.

Contemporary Euro- American culture may be the most aggressive of such frameworks ever implicitly ingrained, because it extends far and deep into other people’s thoughts and sensory experiences.

The extent to which other people’s mental lives are considered “transparent” (and hence knowable) or “

opaque” (and unknowable) is another important difference found across cultures.

In contemporary Euro- America, in addition to thinking of ourselves in

increasingly neurochemical terms, we think and worry excessively about what other people feel and think, and we have slowly incorporated a set of simplified medicalized assumptions and worries about how “normal”, healthy, sick and dangerous other people’s thoughts are.

Add to this a moral panic about a simplified

catalogue of psychopathology, an obsession with self-authorship, and pervasive marketing from pharmacological industries, and the system of domination is almost total, because people will police their own selves before policing others.

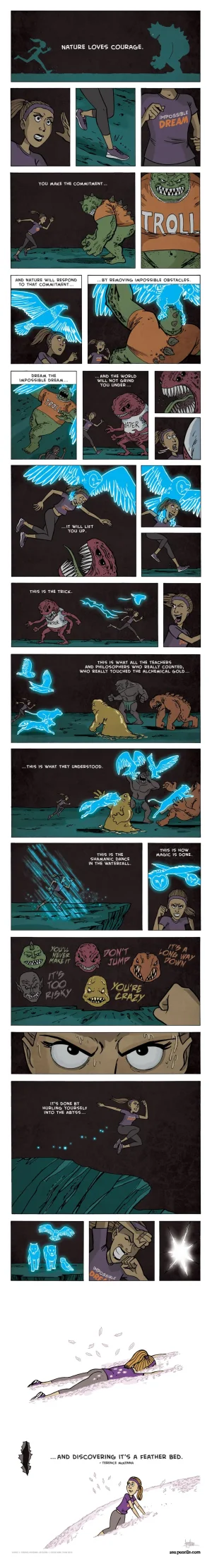

Any private mental experience that departs from this sanitized norm will tend to be self-interpreted as scary and as the potential marker of mental illness. Given this set of problems, it is important to recognize Tulpamancy as a courageous, creative, and mystical backlash to the covert conservatism of our culture.

To sum up, Tulpamancy presents us with a fascinating case study for the study of the embodied and social nature of consciousness and cognition, and the emergence of new forms of culture and subjectivity.

It also offers an important paradigm for revising our simplistic and limiting understanding of mental illness on the one hand, and mental life and personhood on the other.