You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The Lack of Affordable Healthcare in the US

- Thread starter Skarekrow

- Start date

-

- Tags

- healthcare obamacare trumpcare

More options

Who Replied?- MBTI

- INFJ

- Enneagram

- 954 so/sx

the American healthcare system is irrational.

Good word for it

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

As it stands today, the American healthcare system is irrational.

If our country doesn’t burn to the ground first...I can only hope in the future that we have some form of universal healthcare where profit margins are removed.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

A very well-written article outlining what is going on and how dangerous it can be to millions of people...the elderly, children, disabled, and struggling.

Why Trump’s attacks on preexisting conditions are an attack on women

If Democrats take the House, they will have women voters —

and their commitment to protections for preexisting conditions — to thank.

A woman protests Trump administration policies that threaten the Affordable Care Act in Los Angeles.

If Democrats take the House, they will have women voters —

and their commitment to protections for preexisting conditions — to thank.

A woman protests Trump administration policies that threaten the Affordable Care Act in Los Angeles.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

And this is why things have not yet changed.

This is why people are still suffering needlessly.

I know karma doesn’t work like that...but dammit, come on!

Inhuman.

These “people” are truly sick fuck psychopaths.

by John Vibes

April 28, 2018

A report from Goldman Sachs

openly admitted that curing patients

is not a "sustainable business model"

for drug companies.

There has always been some suspicion that pharmaceutical companies would rather keep people sick and on drugs than cure them in one shot and lose the ability to create return customers.

Although the massive motive here is easy to see, with the industry bringing in over $453 billion in the United States alone in 2017, many people have a hard time considering that these companies don't have their customers' best interest at heart.

The idea that these companies would want to keep us sick is dismissed by many as a "conspiracy theory," but let's not forget that these companies and their high-level investors are here to sell drugs, not save lives.

This point was brought up openly earlier this month in a memo that Goldman Sachs analyst Salveen Richter sent out to clients of the firm, about the potential of curing diseases with gene therapy.

Richter estimated the market size for gene therapies could be as large as $4.8 trillion as "genes are the foundations of all biological activity," according to CNBC.

However, he has some concerns about how the ability to cure diseases could negatively impact the industry's bottom line.

In the report, Richter asks the question,

"Is curing patients a sustainable business model?",

...and the conclusion that he seems to come to is "no..."

In the memo, Richter plainly said,

"The potential to deliver 'one-shot cures' is one of the most attractive aspects of gene therapy, genetically-engineered cell therapy, and gene editing.

However, such treatments offer a very different outlook with regard to recurring revenue versus chronic therapies.

While this proposition carries tremendous value for patients and society, it could represent a challenge for genome medicine developers looking for sustained cash flow."

As an example of how cures can be bad for business, Richter pointed to the case of Gilead Sciences, a company that developed a treatment for hepatitis C, which had a cure rate of more than 90 percent.

As Richter pointed out,

"GILD is a case in point, where the success of its hepatitis C franchise has gradually exhausted the available pool of treatable patients.

In the case of infectious diseases such as hepatitis C, curing existing patients also decreases the number of carriers able to transmit the virus to new patients, thus the incident pool also declines…

Where an incident pool remains stable (e.g., in cancer) the potential for a cure poses less risk to the sustainability of a franchise."

It seems as if Richter is suggesting that he would rather people have hepatitis and that he has no interest in the prevention of diseases like cancer.

Next, he suggested that pharmaceutical companies should only focus on diseases that have a steady stream of new customers, such as common inherited and genetical disorders.

The report gave three suggested solutions for drug makers:

But at the end of the report, Richter said,

"Pace of innovation will also play a role as future programs can offset the declining revenue trajectory of prior assets."

While this statement can be interpreted in a number of different ways, it certainly seems that Richter is suggesting that drug makers should slow the pace of development of curesto allow the growth of these new markets to catch up with the level of their current revenue streams.

On a very surface level, it may seem that this is just some toxic manifestation of a selfish human nature or an example of the greed that exists in the world of business, but there is much more nuance to this situation.

Goldman Sachs, along with many other Fortune 500 companies, have a very twisted way of looking at the world and conducting business, because they achieve and attain their success by lobbying for monopoly or cartel-like protections from governments - not by actually providing value to their customers.

Goldman Sachs analysts and Big Pharma executives have a business model that depends on cornering markets with patents and keeping innovation in their industries as stagnant as possible, which is why we see such cut-throat behavior from companies in these positions, but it doesn't have to be this way.

If companies were forced to compete to stay relevant and keep their customers happy, instead of just developing and maintaining government-granted patents and monopolies, innovation would be driven by the desires of the customers, which would keep businesses honest, even if their only intention was to make money.

Goldman Sachs analysts attempted to address a touchy subject for biotech companies, especially those involved in the pioneering "gene therapy" treatment: cures could be bad for business in the long run.

"Is curing patients a sustainable business model?" analysts ask in an April 10 report entitled "The Genome Revolution."

"The potential to deliver 'one shot cures' is one of the most attractive aspects of gene therapy, genetically-engineered cell therapy and gene editing.

However, such treatments offer a very different outlook with regard to recurring revenue versus chronic therapies," analyst Salveen Richter wrote in the note to clients Tuesday.

"While this proposition carries tremendous value for patients and society, it could represent a challenge for genome medicine developers looking for sustained cash flow."

Richter cited Gilead Sciences' treatments for hepatitis C, which achieved cure rates of more than 90 percent.

The company's U.S. sales for these hepatitis C treatments peaked at $12.5 billion in 2015, but have been falling ever since.

Goldman estimates the U.S. sales for these treatments will be less than $4 billion this year, according to a table in the report.

"GILD is a case in point, where the success of its hepatitis C franchise has gradually exhausted the available pool of treatable patients," the analyst wrote.

"In the case of infectious diseases such as hepatitis C, curing existing patients also decreases the number of carriers able to transmit the virus to new patients, thus the incident pool also declines…

Where an incident pool remains stable (e.g., in cancer) the potential for a cure poses less risk to the sustainability of a franchise."

The analyst didn't immediately respond to a request for comment.

The report suggested three potential solutions for biotech firms:

"Solution 1: Address large markets: Hemophilia is a $9-10bn WW market (hemophilia A, B), growing at ~6-7% annually."

"Solution 2: Address disorders with high incidence: Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) affects the cells (neurons) in the spinal cord, impacting the ability to walk, eat, or breathe."

"Solution 3: Constant innovation and portfolio expansion: There are hundreds of inherited retinal diseases (genetics forms of blindness)… Pace of innovation will also play a role as future programs can offset the declining revenue trajectory of prior assets."

This is why people are still suffering needlessly.

I know karma doesn’t work like that...but dammit, come on!

Inhuman.

These “people” are truly sick fuck psychopaths.

by John Vibes

April 28, 2018

A report from Goldman Sachs

openly admitted that curing patients

is not a "sustainable business model"

for drug companies.

There has always been some suspicion that pharmaceutical companies would rather keep people sick and on drugs than cure them in one shot and lose the ability to create return customers.

Although the massive motive here is easy to see, with the industry bringing in over $453 billion in the United States alone in 2017, many people have a hard time considering that these companies don't have their customers' best interest at heart.

The idea that these companies would want to keep us sick is dismissed by many as a "conspiracy theory," but let's not forget that these companies and their high-level investors are here to sell drugs, not save lives.

This point was brought up openly earlier this month in a memo that Goldman Sachs analyst Salveen Richter sent out to clients of the firm, about the potential of curing diseases with gene therapy.

Richter estimated the market size for gene therapies could be as large as $4.8 trillion as "genes are the foundations of all biological activity," according to CNBC.

However, he has some concerns about how the ability to cure diseases could negatively impact the industry's bottom line.

In the report, Richter asks the question,

"Is curing patients a sustainable business model?",

...and the conclusion that he seems to come to is "no..."

In the memo, Richter plainly said,

"The potential to deliver 'one-shot cures' is one of the most attractive aspects of gene therapy, genetically-engineered cell therapy, and gene editing.

However, such treatments offer a very different outlook with regard to recurring revenue versus chronic therapies.

While this proposition carries tremendous value for patients and society, it could represent a challenge for genome medicine developers looking for sustained cash flow."

As an example of how cures can be bad for business, Richter pointed to the case of Gilead Sciences, a company that developed a treatment for hepatitis C, which had a cure rate of more than 90 percent.

As Richter pointed out,

"GILD is a case in point, where the success of its hepatitis C franchise has gradually exhausted the available pool of treatable patients.

In the case of infectious diseases such as hepatitis C, curing existing patients also decreases the number of carriers able to transmit the virus to new patients, thus the incident pool also declines…

Where an incident pool remains stable (e.g., in cancer) the potential for a cure poses less risk to the sustainability of a franchise."

It seems as if Richter is suggesting that he would rather people have hepatitis and that he has no interest in the prevention of diseases like cancer.

Next, he suggested that pharmaceutical companies should only focus on diseases that have a steady stream of new customers, such as common inherited and genetical disorders.

The report gave three suggested solutions for drug makers:

- "Solution 1 - Address large markets: Hemophilia is a $9-10bn WW market (hemophilia A, B), growing at ~6-7% annually."

- "Solution 2 - Address disorders with high incidence: Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) affects the cells (neurons) in the spinal cord, impacting the ability to walk, eat, or breathe."

- "Solution 3 - Constant innovation and portfolio expansion: There are hundreds of inherited retinal diseases (genetics forms of blindness)"

But at the end of the report, Richter said,

"Pace of innovation will also play a role as future programs can offset the declining revenue trajectory of prior assets."

While this statement can be interpreted in a number of different ways, it certainly seems that Richter is suggesting that drug makers should slow the pace of development of curesto allow the growth of these new markets to catch up with the level of their current revenue streams.

On a very surface level, it may seem that this is just some toxic manifestation of a selfish human nature or an example of the greed that exists in the world of business, but there is much more nuance to this situation.

Goldman Sachs, along with many other Fortune 500 companies, have a very twisted way of looking at the world and conducting business, because they achieve and attain their success by lobbying for monopoly or cartel-like protections from governments - not by actually providing value to their customers.

Goldman Sachs analysts and Big Pharma executives have a business model that depends on cornering markets with patents and keeping innovation in their industries as stagnant as possible, which is why we see such cut-throat behavior from companies in these positions, but it doesn't have to be this way.

If companies were forced to compete to stay relevant and keep their customers happy, instead of just developing and maintaining government-granted patents and monopolies, innovation would be driven by the desires of the customers, which would keep businesses honest, even if their only intention was to make money.

'Is Curing Patients a Sustainable Business Model?'

Goldman Sachs asks in Biotech Research Report

by Tae Kim

April 11, 2018

from CNBC Website

Goldman Sachs asks in Biotech Research Report

by Tae Kim

April 11, 2018

from CNBC Website

Goldman Sachs analysts attempted to address a touchy subject for biotech companies, especially those involved in the pioneering "gene therapy" treatment: cures could be bad for business in the long run.

"Is curing patients a sustainable business model?" analysts ask in an April 10 report entitled "The Genome Revolution."

"The potential to deliver 'one shot cures' is one of the most attractive aspects of gene therapy, genetically-engineered cell therapy and gene editing.

However, such treatments offer a very different outlook with regard to recurring revenue versus chronic therapies," analyst Salveen Richter wrote in the note to clients Tuesday.

"While this proposition carries tremendous value for patients and society, it could represent a challenge for genome medicine developers looking for sustained cash flow."

The company's U.S. sales for these hepatitis C treatments peaked at $12.5 billion in 2015, but have been falling ever since.

Goldman estimates the U.S. sales for these treatments will be less than $4 billion this year, according to a table in the report.

"GILD is a case in point, where the success of its hepatitis C franchise has gradually exhausted the available pool of treatable patients," the analyst wrote.

"In the case of infectious diseases such as hepatitis C, curing existing patients also decreases the number of carriers able to transmit the virus to new patients, thus the incident pool also declines…

Where an incident pool remains stable (e.g., in cancer) the potential for a cure poses less risk to the sustainability of a franchise."

The analyst didn't immediately respond to a request for comment.

The report suggested three potential solutions for biotech firms:

"Solution 1: Address large markets: Hemophilia is a $9-10bn WW market (hemophilia A, B), growing at ~6-7% annually."

"Solution 2: Address disorders with high incidence: Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) affects the cells (neurons) in the spinal cord, impacting the ability to walk, eat, or breathe."

"Solution 3: Constant innovation and portfolio expansion: There are hundreds of inherited retinal diseases (genetics forms of blindness)… Pace of innovation will also play a role as future programs can offset the declining revenue trajectory of prior assets."

Roses In The Vineyard

Well-known member

- MBTI

- INFJ

https://www.zerohedge.com/news/2018-07-27/heres-how-systems-and-nations-fail

Would any sane person choose America's broken healthcare system over a cheaper, more effective alternative? Let's see: the current system costs twice as much per person as the healthcare systems of our developed-world competitors, a medication to treat infantile spasms costs $8 per vial in Europe and $38,892 in the U.S., and by any broad measure, the health of the U.S. populace is declining.

This is how systems and nations fail: nobody chose the current broken system, but now it can't be changed because the incentive structure locks in embedded processes that enrich self-serving insiders at the expense of the system, nation and its populace.

Nobody chose America's insane healthcare system--it arose from a set of initial conditions that generated perverse incentives to do more of what's failing and protect the processes that benefit insiders at the expense of everyone else.

In other words, the system that was intended to benefit all ends up benefitting the few at the expense of the many.

The same question can be asked of America's broken higher education system:would any sane person choose a system that enriches insiders by indenturing students via massive student loans (i.e. forcing them to become debt serfs)?

Students and their parents certainly wouldn't choose the current broken system, but the lenders reaping billions of dollars in profits would choose to keep it, and so would the under-assistant deans earning a cool $200K+ for "administering" some embedded process that has effectively nothing to do with actual learning.

The academic ronin a.k.a. adjuncts earning $35,000 a year (with little in the way of benefits or security) for doing much of the actual teaching wouldn't choose the current broken system, either.

Now that the embedded processes are generating profits and wages, everyone benefitting from these processes will fight to the death to retain and expand them, even if they threaten the system with financial collapse and harm the people who the system was intended to serve.

How many student loan lenders and assistant deans resign in disgust at the parasitic system that higher education has become? The number of insiders who refuse to participate any longer is signal noise, while the number who plod along, either denying their complicity in a parasitic system of debt servitude and largely worthless diplomas (i.e. the system is failing the students it is supposedly educating at enormous expense) or rationalizing it is legion.

If I was raking in $200,000 annually from a system I knew was parasitic and counter-productive, I would find reasons to keep my head down and just "do my job," too.

At some point, the embedded processes become so odious and burdensome that those actually providing the services start bailing out of the broken system. We're seeing this in the number of doctors and nurses who retire early or simply quit to do something less stressful and more rewarding.

These embedded processes strip away autonomy, equating compliance with effectiveness even as the processes become increasingly counter-productive and wasteful. The typical mortgage documents package is now a half-inch thick, a stack of legal disclaimers and stipulations that no home buyer actually understands (unless they happen to be a real estate attorney).

How much value is actually added by these ever-expanding embedded processes?

By the time the teacher, professor or doctor complies with the curriculum / "standards of care", there's little room left for actually doing their job. But behind the scenes, armies of well-paid administrators will fight to the death to keep the processes as they are, no matter how destructive to the system as a whole.

This is how systems and the nations that depend on them fail.

Would any sane person choose America's broken healthcare system over a cheaper, more effective alternative? Let's see: the current system costs twice as much per person as the healthcare systems of our developed-world competitors, a medication to treat infantile spasms costs $8 per vial in Europe and $38,892 in the U.S., and by any broad measure, the health of the U.S. populace is declining.

This is how systems and nations fail: nobody chose the current broken system, but now it can't be changed because the incentive structure locks in embedded processes that enrich self-serving insiders at the expense of the system, nation and its populace.

Nobody chose America's insane healthcare system--it arose from a set of initial conditions that generated perverse incentives to do more of what's failing and protect the processes that benefit insiders at the expense of everyone else.

In other words, the system that was intended to benefit all ends up benefitting the few at the expense of the many.

The same question can be asked of America's broken higher education system:would any sane person choose a system that enriches insiders by indenturing students via massive student loans (i.e. forcing them to become debt serfs)?

Students and their parents certainly wouldn't choose the current broken system, but the lenders reaping billions of dollars in profits would choose to keep it, and so would the under-assistant deans earning a cool $200K+ for "administering" some embedded process that has effectively nothing to do with actual learning.

The academic ronin a.k.a. adjuncts earning $35,000 a year (with little in the way of benefits or security) for doing much of the actual teaching wouldn't choose the current broken system, either.

Now that the embedded processes are generating profits and wages, everyone benefitting from these processes will fight to the death to retain and expand them, even if they threaten the system with financial collapse and harm the people who the system was intended to serve.

How many student loan lenders and assistant deans resign in disgust at the parasitic system that higher education has become? The number of insiders who refuse to participate any longer is signal noise, while the number who plod along, either denying their complicity in a parasitic system of debt servitude and largely worthless diplomas (i.e. the system is failing the students it is supposedly educating at enormous expense) or rationalizing it is legion.

If I was raking in $200,000 annually from a system I knew was parasitic and counter-productive, I would find reasons to keep my head down and just "do my job," too.

At some point, the embedded processes become so odious and burdensome that those actually providing the services start bailing out of the broken system. We're seeing this in the number of doctors and nurses who retire early or simply quit to do something less stressful and more rewarding.

These embedded processes strip away autonomy, equating compliance with effectiveness even as the processes become increasingly counter-productive and wasteful. The typical mortgage documents package is now a half-inch thick, a stack of legal disclaimers and stipulations that no home buyer actually understands (unless they happen to be a real estate attorney).

How much value is actually added by these ever-expanding embedded processes?

By the time the teacher, professor or doctor complies with the curriculum / "standards of care", there's little room left for actually doing their job. But behind the scenes, armies of well-paid administrators will fight to the death to keep the processes as they are, no matter how destructive to the system as a whole.

This is how systems and the nations that depend on them fail.

pzl2lxie81mc

Donor

- MBTI

- INFJ

It’s not the days of Jonas Salk anymore, who decided against patenting his polio vaccine so that more people can become inoculated.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Pity curing diseases has turned from an altruistic mission into a cash cow for investors who could care less about the suffering they are responsible for.It’s not the days of Jonas Salk anymore, who decided against patenting his polio vaccine so that more people can become inoculated.

Why bother taking the Hippocratic oath at all?

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

I'm getting impatient with Democratic politicians, most of whom don't support Medicare for all.

Some Left-Wing party.

It really can't be passed on the local or state level? Come on.

Slow as molasses.

It can...such as MediCal in CA, or here in WA state they have passed laws protecting the ACA provisions the GOP is torpedoing.

The Dems are frustrating...the whole of Congress is out of touch with the common person - minus a few here and there.

The majority of them are millionaires if not richer...have no clue what things cost in the real world or what it means to live paycheck to paycheck.

I just got my bill for a series of injections - they changed my insurance $13,000 for 4 injections...not even IV infusions...regular injections.

It was a very specific drug mind you, but that is fucking crazy.

I wasn’t supposed to have to pay anything but now I’m stuck writing the hospital to see if they will write off the amount they are billing me ($1300) since I was told I would pay nothing and the whole point of going here and not through the pharmacy was to make it affordable to try the drug.

So much for affordable.

After having my two surgical procedures at the beginning of the year, the amount providers have billed to my insurance total so far this year is $102,352.46.

WTF

Imagine having to pay out of pocket?

Someone is getting fucking rich with those charges.

What a racket.

Still...I wish people were smarter about the whole idea.

Medicare for all would be a gigantic help for most people...if people still want to buy rider plans, then let them.

What’s the problem...I guess people enjoy going bankrupt from being injured or ill.

But of course...we have to pay for things like $93 million+ military parades for the POTUS dickhead.

(On hold...thanks)

Can’t afford it...rich people wouldn’t be as rich!

The fleecing of the workers is not complete yet...there is still some blood to squeeze from the stone.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Dark Robespierre: "We have lots left. How many do you need?"

Just one....which ever has the dullest blade.

(Muhahahaha)

Ren

Seeker at heart

- MBTI

- INFJ

- Enneagram

- 146

Just one....which ever has the dullest blade.

(Muhahahaha)

*whispers* French kings Philip IV and Louis XI have other cool ideas... ever heard of the fillettes?

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

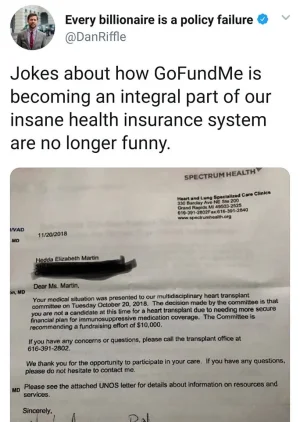

"Sorry...but you just can’t afford to continue living without a $10,000 deposit.Not to mention that Spectrum Health is owned by the Billionaire DeVos family.@Ren

Disgusting.

You guys still have some guillotines left over?

We only take cash and/or your first born infant.”

The people who wrote this letter are far sicker in the head than the person they are denying a working heart to.

Hmmm....maybe if they had...idk.....A WORKING HEART...they would be able to work and have a job where they could afford such things as transplant surgery.

Killing the poor...one rejection letter at a time.

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

Yes!*whispers* French kings Philip IV and Louis XI have other cool ideas... ever heard of the fillettes?

And...I propose a machine of whirling cheese graters!

Skarekrow

~~DEVIL~~

- MBTI

- Ni-INFJ-A

- Enneagram

- Warlock

*whispers* French kings Philip IV and Louis XI have other cool ideas... ever heard of the fillettes?

Not even surprised anymore that a meme already exists for this conversation ahahaha